An excerpt from ‘Iranshah: A Legacy Restored’, by Zarin Amrolia.

Article by Zarin Amrolia | Scroll

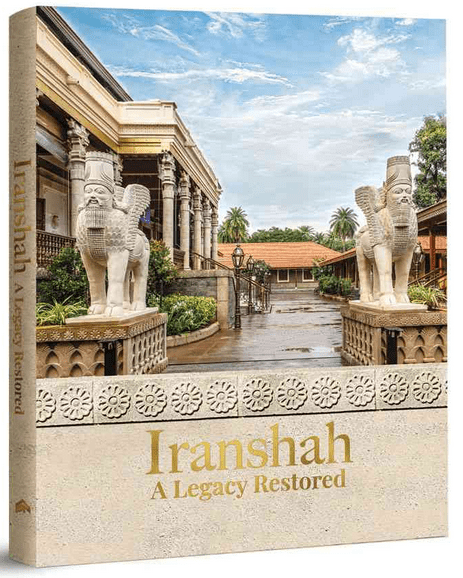

Iranshah Ātash Behram temple in Udwada, Gujarat. | Divya Cowasji.

An evening walk through the town gives one an opportunity to stop and greet the mobeds (ordained priests) who have made Udwada their home for many generations. In their flowing white muslin jamas (robes), their heads covered in paghris (turbans), and a padan of fine mull cloth covering the nose and mouth, they serve the divine fire several times a day. They are also often requested to pray for the souls of departed family members and conduct ceremonies in gratitude for celebratory events.

Most of the permanent residents of Udwada are members of the nine families who have been serving as boiwalas (priests who tend to the fire) at the Iranshah Atash Behram for generations. Ervad Kekobad Mogul belongs to one of these nine families and is the seventh generation of a family to make Udwada their home. Today, he is the most experienced boiwala, having spent seventy years bowing to the revered fire five times a day. “My family has been serving the Iranshah since the Maratha regime. The earliest was Ervad Bhikha Dastur Rustom,” says Ervad Mogul.

Dressed in white always, the octogenarian navigates his way to the Iranshah Atash Behram every morning on his trusted bicycle, and claims that the power of the manthravani (prayers) is immense for those who have faith. Much respected for his knowledge in conducting rituals and much loved for his good humour, he is often consulted by Zoroastrian priests and academicians. “Everyone is surprised to see me still working part-time. And I tell them, it is all by the grace of the Iranshah,” he says.

Numerous portraits of his venerable ancestors grace his quaint house. One afternoon he and his wife, Freny Mogul, were our gracious hosts, as he recalled memories of being a full-time priest at the Atash Behram with wit, joviality and satisfaction at being part of such a distinguished legacy.

“My life is dedicated to the service of my Atash Padshah. l became a navar (first level of priesthood) while I was in school. Before becoming a navar, our senior mobeds would test us to discover how well we knew our prayers. By the age of ten, I had learnt all the prayers of the higher liturgical ceremonies of Ijeshne, Vendidad and Visperad which are extensive. The mobeds who took my test predicted that I would be performing these ceremonies until it was time to retire, and I did!” Ervad Mogul laughed, crediting his father for the knowledge he imparted to him.

“My father supported me immensely, and I am continuing his legacy. As a full-time priest, I would conduct the boi ceremonies of all five gahs (the day is divided into five periods or gahs), beginning from the midnight Ushahin gah. In my lifetime, I have conducted thousands of pav mahal (high inner liturgical ceremonies) prayers such as Ijeshne and Vendidad which last for hours and there is no break for drinking water or visiting the restroom.” On the days he was on duty, his resting place at home would be a cot which was kept secluded from all.

Maintaining such a devout lifestyle is only possible with the help of family who believe in the cause. “My wife has followed every ritual and offered me support to carry on with my work,” Ervad Mogul acknowledges.

He is a firm believer in the divine power of the Iranshah. “Our Atash Padshah was consecrated in Sanjan, and for the first seven hundred years there, the aura of lranshah was such that only the spiritually enlightened would be able to see the full glory of the fire, while for us perhaps a small part of the fire was visible.”

He is witness to thousands of Zoroastrians from far and wide paying their respects at the Ätash Behram. “You must have faith. Faith moves mountains. In my seventy years as a full-time priest, I have seen many miracles.”

To become a “perfect” mobed, education in religious methods is required. The first step is to become a navär, then a marätab and then a samel. “Samel means being a perfect mobed. When we complete all our education, we reach out to the senior mobeds to take our exam. For this exam, forty or fifty senior mobeds as well as Dasturjis test the aspiring young priests on several prayers, and rituals,” said Elvad Mogul. Citing the example of one such ritual he said, “We have to cut our own hair as a barber cannot touch us. There is a prayer and ritual before and after taking haircuts, consuming food and daily baths.” Those who excel must undergo the seclusion of a sacred nähn (purification ceremony) for nine days and nine nights and conduct the required rituals. And then it is announced that the student is ready to conduct all ceremonies.” Not all the mobeds excel in the first round. If a candidate does not fare well, he is requested to continue studying for another six months before he can reappear for the exam.

“Earlier, we used to have around forty students who would study to become perfect mobeds. Over the years, these young children grew up to become engineers, and doctors and joined other professions where they would excel. Many of them, after their retirement, have come back to give boi at the Iranshah. Today, we need them. Previously, there would be twelve to fourteen mobeds from each of the nine families, now there are only one or two practising priests. My brothers too know all the ceremonies and prayers although they are not practicing priests. The number of mobeds has reduced and perfect mobeds like us are even fewer,” Ervad Mogul says regretfully.

Gratitude, appreciation, and faith imbued the conversations. The opportunity to serve the Iranshan he says is a blessing. “I have served the Iranshah for seventy years, day and night. Now I am retired, but still pray at Iranshah every day. Today, I am satisfied, happy and grateful to dedicate my life to my Atash Padshah.

Excerpted with permission from Iranshah: A Legacy Restored, Zarin Amrolia, Shapoorji Pallonji and Company Private Limited.