A photograph taken seven years before her passing says much about the life, times and character of the trailblazing Meherbai Tata

The much-loved wife of Dorabji Tata and daughter in-law of Jamsetji Tata, the founder of the Tata group, Meherbai Tata was a woman of personality. A participant in the ornamental theatrics of being imperial within Empire, one finds her name regularly among the maharajas, nawabs and begums in royal chronicles. And deservedly so.

Meherbai was honoured with the ‘Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire’ (CBE) in 1916 for her philanthropic efforts in service of the Crown during World War I. She hosted Queen Anne, along with Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, at her home. She was India’s first woman Olympic athlete — at the 1924 Paris games, although her name is missing from India’s records — and the first Indian woman to fly in an airplane (in 1912). As founder of the National Council for Women in India, she fought for the ‘modern’ educated Indian woman.

Article by Sneha Vijay Shah | Horizons Tata Trust

is an art historian, curator and arts entrepreneur. She divides her time between London and Mumbai

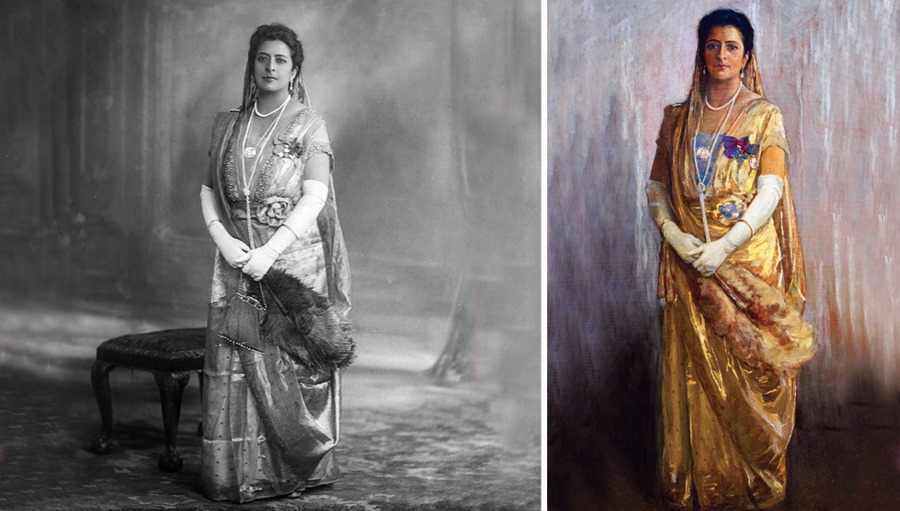

The Lafayette Studio photograph of Meherbai Tata from 1924 and, commissioned after her death, the painting based on it (Images courtesy: © Victoria and Albert Museum, London (above left), and, Trustees, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, Mumbai)

In the midst of a global pandemic, with grief and loss surrounding us, the time is perhaps apt to ask the hereafter questions. What becomes of us once we leave this realm? How would we like to be remembered? What happens to our legacy, our life’s work, the impact we make through our time in this world?

Photographs and portraits have long been used as a way to remember our ancestors and loved ones. Such remembering was not as straightforward in Meherbai’s day as it is now. The process of being photographed took far too long for the possibility of candid captures. One would carefully choose a photo studio, attire, props and then strike a calculated pose as the camera registered the image. Photographs images from this period, thus, represent the stories the people posing wanted to tell about themselves, how they hoped to be seen and remembered.

As an art historian, I research how such archived portrait photographs, when interpreted through the lens of art history, can recover ‘lost identities’. In the case of Meherbai, the photographs illuminate the private, the public and the political, as also the life, times, achievements and insecurities of a once dominant woman who belonged to one of the most powerful industrial families of India. The attempt here is to uncover the secrets hidden within Meherbai’s official portrait.

On 27 June, 1924, Lady Meherbai Dorab Tata walked into The Lafayette Studio at 160 New Bond Street, London, for her official photograph, possibly on the occasion of being summoned to court at Buckingham Palace. The studio had built a reputation as portrayers of a rich and powerful empire and had been decreed the title of ‘Photographer Royal’. The warrant was a magnet for the studio’s clientele, among them India’s royals and other eminences. These dignitaries flocked to Lafayette for the explicit purpose of having an ‘official portrait’ made.

‘Court’ attire

Within the black-and-white frame of her glass negative, located in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s archives in London, Meherbai looks ethereal. In the Lafayette archives, translated from plate into printed form, within the transferred image the light changes immediately (see image on page 68). One’s gaze is drawn towards her white gloves — the whitest element of the portrait — the very piece of her outfit that makes it definitive English ‘court’ attire. A gold bangle, with intricate leaf motives, traditional to Indian dressing, sits subtly over her gloves on each hand.

Meherbai appears dressed in a crisply ironed satin-silk sari, the folds still visible around the skirt. The image reveals photography’s ability to capture the unintended. The ironing around her hip gives way to crumpling. She probably arrived at the studio wearing the outfit — no easy task — and she would have had to climb up the three flights of stairs to the top floor studio, where the cumbersome equipment of the photographic trade would have been waiting for her.

A little rosette sits upon Meherbai’s waist, and it pieces together two eclectic elements of her outfit: the Edwardian blouse with a V-neck and her sari. The pallu (loose end of the sari) gracefully drapes her combed bun before flowing in the Parsi-Gujrati style to the front. Meherbai’s attire immediately identifies her as an Indian, somebody with knowledge of western fashions. Her hands come to a close, right hand tucked within her left, as she holds an ostrich feather plume and Indian batwa (purse) within her palms. Her dual allegiance to India and the Crown is evident.

For Meherbai, the ‘national sari’ was almost obsessively a patriotic symbol. She wore it while driving a motorcar or riding a horse, even at tennis tournaments. Furthermore, she was noted to have — in the words of Stanley Reed, then editor of The Times of India “regarded with some impatience the younger members of her community who discarded the traditional costume for Western modes”. In an address delivered at Battle Creek College on November 29, 1927, she stated proudly while drawing attention to her attire: ‘This is the sari, the dress that I wear. The sari was never worn in Persia, but we have modified it a good deal and we wear it a little differently from the Hindu ladies from whom we took the dress”.

By the early 1920s, the sari had emerged in India as a political garment, helped along by Gandhi’s push for women — as “mothers of Indian industry” — to give up foreign consumption and switch to Khadi fabrics. Meherbai’s choice of modified court dress, an amalgamation of the Indian-Gujrati sari draped over an Edwardian-fashioned bodice with a plunging neckline, is intriguing within this political context. It occupies a threshold position, much like her in society, between the English and the Indian.

Meherbai accessorises her outfit with her ‘Jubilee diamond’ pendant necklace, named after Queen Victoria’s centenary anniversary. This is set in a platinum claw and hung on a thin platinum chain, surrounded by a double-chain pearl necklace that extends to her torso. At 245 carats, after being cut and polished, the diamond is twice as large as the Koh-I-Noor, that vexed icon of colonial plunder.

Found in a South African mine in 1895, the Jubilee diamond was acquired by a consortium of London diamond merchants. During the cutting and cleaning process, the consortium realised the brilliance of the diamond and planned for it to be presented to Queen Victoria as a gift on the occasion of her ‘jubilee anniversary’ in 1896. This did not happen for some reason.

The consortium decided to display the diamond at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris. It is here, in the centre of much hype and attention, that Meherbai and Dorab Tata ‘shopped’ for it. ‘Shopping’ at the Paris expositions was almost a tradition within the Tata family. In 1878, Jamsetji Tata brought from his trip much that fascinated him, including animals that he kept at his zoo in Navsari and the spun-iron pillars that till today hold up the ballroom of the Taj Mahal Hotel in Mumbai.

The Jubilee, which holds the rank of the sixth-largest diamond in the world, was purchased by Meherbai and Dorab for £100,000. Every time the Tatas removed it from their safe deposit vault in London for Meherbai to wear it, they were reportedly ‘fined’ £200 by the insurance company. Posing confidently with the Jubilee, a gift for the queen within this portrait, one cannot help but wonder how the diamond might have been received as part of her garb in court at Buckingham Palace.

Diamond for a cause

The Jubilee was part of the jewellery pledged by Dorab Tata to the Imperial Bank when the Tata Iron and Steel Company (TISCO) was undergoing a crisis in 1924. The diamond was eventually sold following Meherbai’s demise from leukaemia, along with the rest of her jewellery, to set up the Lady Meherbai Tata Trust for cancer research and women’s education.

Coming back to the portrait, upon Meherbai’s lapel, almost camouflaged by the gradient of her sari, is her CBE badge. The award was instituted by George V to reward military and civilian wartime service to the Empire. It was almost a bribe to draw elite members of the colonies to help the imperial war effort. As Parsis with no title of their own, the CBE and other similar honours may have been the only way for them to gain the social clout to match their growing business power.

Unlike many of her female counterparts, Meherbai is careful not to lean on or take the support of any props in her portrait, an authoritative pose that marks her unconventional individuality. Meherbai stages herself as youthful, stands tall and poised, showcasing the grace, dignity and athletic spirit she was bred to embody. She is proud of her figure — Lafayette’s ‘retouchers’ were experts at bringing in waists and correcting arm widths, but Meherbai seems to have excused herself from such services — she is self-aware and confident.

The portrait’s backdrop is painted in a style typical of the period’s fashions, blurred out like the background of a Rembrandt painting. Lafayette’s expert team ensured that Meherbai, even embellished with all her adornments, is the only distinguishable subject. One sees a hint of a frame with a western balcony sneaking through. The only studio prop seen is a stool in the middle ground that partially hides behind Meherbai, its purpose seemingly to ground her within the composition.

The lighting is dramatic and Meherbai’s expression austere. She is well aware of her beauty, a notion that during this period alluded in part to a fair complexion. As Persians, Parsis were not as ‘white’ as Europeans, and not as dark as Indians. They held an in-between position even in this aspect. Meherbai doesn’t have to hide behind her colour. Her complexion is in fashion.

The Tatas were certainly proud of Meherbai’s portrait. It is the one the family chose to convert into an oil painting, upon her death, to immortalise her memory (see image on page 68). Queen Victoria’s court painter, John Lavery, was employed for the commission. Curiously, Meherbai’s batwa is missing from the painting’s composition.

Within the portrait, colour is brought to Meherbai’s skin and garb. She materialises as a manifestation of Reed’s description of her: “Above medium height, clear cut, and clear-eyed, with that flush through the faintly tinted olive skin…”