Zoroastrian, Shia Muslim (Yazdi and Shirazi) and Baha’i Iranian migrants, and of course the Palanpur-hailing Cheliyas, have been feeding this city for over a century with cheap eats and colourful words

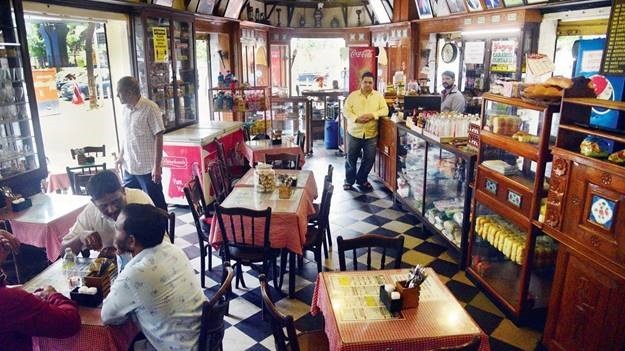

Like Amir Khaon Koolarzade’s father, Mandoh Hussain, most Irani migrants coming into Bombay worked their way up from being kitchen boys to managers to owners, all within one generation. Koolar and Co. at Matunga Circle is now run by him and brother Ali. Pic/Pradeep Dhivar

Article by Mitali Parekh | Mid-Day

If I wanted to cheat you, I’d smile,” Amir Khaon Koolarzade tells customers at his cafe that sits at Matunga Circle when they admit they have rarely seen him smile. He may be the poster child of the grumpy Irani man at the galla (billing counter), but his eyes well up easily several times during our conversation.

His father, Mandoh Hussain, came from Taft village in Yazd province to Mumbai as a nine-year-old with his three brothers. “Their father had died and there was a great famine [in Iran]. My mother said that villagers were subsisting on the grass in their orchards, and their skin had turned green. His father had died and my grandmother was a woman of such pride that she would keep a pot of water boiling on the stove [the smoke rose out the chimney], so that no one would suspect they were out of food and offer charity.”

Proud. Hard working. Straight-talking. Ziddi. Community-minded. Cantankerous. Iranians of all sects—Zoroastrian, Shia Muslim (Yazdi and Shirazi), and Baha’i have been the lifeblood of Bombay’s economy of the street, so vital to fuelling a growing metropolis.

Long after the first waves of Zoroastrians or Zarthoshtis—later to be identified as Parsis—landed on the shores of Gujarat between the 8th and 10 centuries, Iranians continued to migrate to India in spurts. Undivided India shared a border with Iran, and trade routes over centuries. The Silk Route passed through Yazd and Kerman cities. In the 19th century, India was still under British colonial rule, which also wielded great influence in Persia, facilitating movement of the population to port towns of Karachi and Bombay.

The Cheliya Muslims of Gujarat later took over Irani cafes, and mainly worked in the HMT trade (hotels, motoring and tabelas), says Simin Patel. Pic/Ashish Raje

Around 1846, Imam Hasan Ali Shah Aga Khan, the head of the Nizari Ismaili Muslims, moved to Bombay too. The Hindus in the sub continent who had converted to Nizari Ismailism, mostly from the Lohana mercantile caste, were called Khojas. The Ismailis were a wealthy, successful community, and quickly established a network. The noblesse-adjacent families were entrenched in horse trade. Around their mosques and community spaces grew a print and religious economy—amulets, books, pamphlets and other paraphernalia of worship began to be sold.

“From the late 1700s,” says historian Simin Patel, “small family units of Zoroastrians migrated from Persia—fleeing abduction, conversion, and economic hardship—and were absorbed by Parsi households in Bombay. There was a big wave of migration in 1871-72 during the great famine of Persia. Parsi communities in China, Pune, Surat, Bombay, and other pockets of the subcontinent sent financial aid through an Irani firm in Bombay called Godrez Mehrban & Co., and also assisted the families that arrived in India. Asylums were built to accommodate the migrants in the city.”

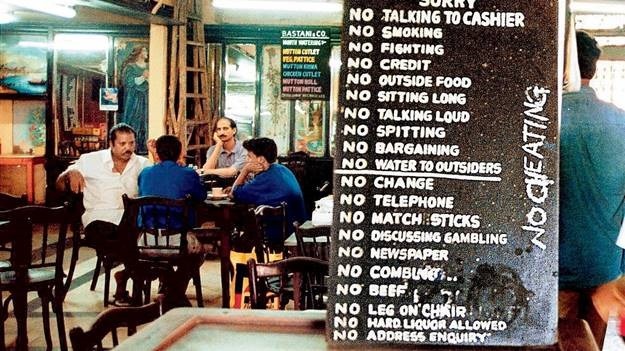

Amir Koolarzade says the long list of rules displayed inside cafes came from an attempt to keep the cafe clean. With mirrors (then rare), a washbasin with soap, towel and comb, the working man could spiff up before taking on the day. Pic/Ashish Raje

The Parsi community that already existed in the sub continent saw these “Persian Parsees”, as one newspaper report of the time referred to them, as country cousins. While there is much affection and kinship, there has been an underlying strain of otherness. “They [Iranians] were not as educated or suave, and were mostly employed as domestic help, as gardeners in Towers of Silence, hygiene staff in eateries or as dishwashers,” Patel adds. “You could distinguish them by their names. They were decidedly more Persian. The men had more Persian sounding names such as Rasheed.”

Within the Iranians, is the smaller sect of Baha’is who follow a relatively new religion dating back to 19th century Iran, and believes in the oneness of humanity and devoting itself to the abolition of racial, class, and religious prejudices. Koolarzade says that the Iranian Zoroastrians consider them more Semite than Persian, given that the Baha’i religious centre is in Haifa, Israel. However, many Baha’i Iranians continue to be part of the community’s fabric. Eventually, 80% of the community’s last names were homogenised to ‘Irani’; until some of them reclaimed their identity and moulded their second names to indicate their place of origin in Persia. “Parsi last names [on the other hand] were affiliated to the trade they practiced [Contractor, Merchant, Engineer, Daruwala], or were anglicised or had European etymology (Petit, Jejeebhoy),” says Patel. Koolar & Co. Restaurant and Stores takes its name from the family name Koolarzade, which comes from the Persian word for ram, koolar. In Taft, the family were shepherds.

Amir Koolarzade

Then, in the 1920s and ‘30s, Muslim Iranians, mostly from Yazd province, came to India, like the Koolarzades. “My grandmother sent her four sons to India with someone from the village. People were often smuggled in oil tankers or on boats,” says Amir. “All the boys found jobs with Iranis trading along the Mazgaon docks. My father washed dishes and served chai at a tea-stall; his younger brother was a hamaal who loaded sacks. Tea stalls opened at 5 am, and my father was up before dawn to brew it.”

All the various kinds of Iranis, irrespective of their religion, achieved their Bombay dream within one generation.

“Most of the men worked their way up in the restaurants, finally graduating to partnership,” says Patel. “They earned incomes by being “sleeping partners” as opposed to “conducting partners” in other restaurants, bakeries and canteens. They prospered enough to send the next generation to elite boarding schools in hill stations across India.”

The Irani chai became the lifeblood of Bombay’s working class heroes, along with a plate of hearty non-vegetarian slop and pao. A new migrant from Iran would be assured of a free plate of food, and opportunities to work and network at most cafés. Pic/Sayed Sameer Abedi

The Koolarzade brothers worked their way around the city, earning variously R2.5, R7 and R5 per month. “For 18 years, my father ate only kela-pao [banana-bread] so that he could send money to his mother and sisters in Iran. The pao cost next to nothing as Iranis baked it themselves. Banana was the cheapest food available,” says Amir. “He was educated somewhat in Persian, but his seths discouraged him from practicing math in his free time. No one wants an educated servant. He got himself a tutor at the age of 30 to learn English. His eldest brother was a bit more educated, and would handle the cash counters at other cafés.”

Koolarzade shares that at one point, his father worked at the notorious Foras Road. “The sex workers would quickly lather him up at the communal null [tap], pour water down his head and send him off to work. He had one lungi with which he would dry himself and wear again.”

As hard as life in Bombay was, home was a remote village where the only transport available back then was a bus that came once a week. “If you were ill, you either waited for it, or carried your sibling on your back and walked 17 kilometres to the doctor,” says Koolarzade. “You farmed honey, reared sheep and hen, and grew fruits. When a hen laid an egg, my grandmother would go exchange it at the bania for two sheets of foolscap paper. Then she could write a letter to send with someone going to India. On this end, the brothers would send her money the same way. Hawala agents would carry it to Taft, if there was anyone going that way, and take a commission.” Mandoh never forgot this: He would recycle paper, collecting the blank pages from his sons’ schoolbooks at the end of the year, and use them for accounts. If they had written on them in pencil, he would make them erase it. His elder son, who moved the hand of a sleeping labourer using his foot once, felt the flat of Mandoh’s palm across his face. “You don’t know what it is to be exhausted after a day of hard labour,” he had said.

Eventually, Mandoh ended up working at George the IV Cafe under Javed Nunwa (‘noon’ for naan) in a building that belonged to the Bhiwandiwala Trust. As partition loomed, the Bhiwandiwalas looked to wrap up their businesses and real estate and move to Pakistan. Their corner properties, considered inauspicious as per Vastu Shastra by Hindus, were becoming hard to sell.

“He offered it to my father for Rs 14,000,” says Koolarzade, “My father had guts and convinced his brothers to pool in and buy it.” The eldest brother, Haaji Mohammed Ali, tore up the piece of paper that listed how much each brother had contributed. “Everything will be divided equally,” he said. Mandoh could cook and was assigned the kitchen; Zafar sat behind the counter and the youngest brother served tables. “Zafar Ali was so fair and rosy cheeked that people used to come to see the ‘laalmooh-walla seth’.”

One by one, the Koolarzades opened seven more cafés, store rooms, bought up plots of marshy land in Matunga for Rs 18 per vaar [1 square yard], and eventually all of Noor Mahal, the building that now holds their cafe, for Rs 40,000. “It was the same thing with apartments,” says Koolarzade, “No one wanted the corner, triangle-shaped properties. Iranis, on the other hand, saw the business potential of nakas [corners that could be accessed by multiple streets].” All corners were landmarks for people to meet or alight from trams, and decide where to go. It made sense to serve a hot cup of tea here.

Slowly, the street food economy grew. “Most Irani cafe have a little wedge in the facade, which would be rented to a paanwala from UP,” points out Patel, “So there was additional income there, plus it promised thorough fare. Cigarettes were also sold at the paanwala as well as at the counter of the Irani. Iranis such as Koolarzades were wholesalers.”

Irani cafés had expensive Belgian mirrors (a rarity in those days), a washbasin with soap and a comb “so that people could groom themselves before going to work,” explains Koolarzade. Which is where the long list of “Nos” the establishments are notorious for displaying on hand-painted boards comes from. Iranis also served eggs and non-vegetarian fare, a rarity then, and opened early in the morning and shut late at night—catering to the ladies of the night and early bird labourers. They also did not shoo away people for not being of a particular caste. “When Zafar Ali become the first president of the Restaurants Association of Bombay, he did away with the coloured rings at the bottom of cutting chai glasses which designated customers as belonging to different [socio-economic] classes.”

The Iranis also conquered auxiliary services—store rooms, bakeries that made naan and pao. When Koolarzade’s grandmother Kaukan Khanum came to live in India for a couple of years, she made sodas in their flat. “We would sell about 20 cartons of soda a month. Cafes would keep them for people suffering indigestion; the rich used it with their drinks.” A deciding factor for the success of the Iranis was their resolve never to offend their hosts. “Iranis still don’t serve pork or beef,” says Koolarzade. “It’s even listed in my lease contract.” The eldest Koolarzade brother, Hajji Mohammad Ali, was stabbed out of revenge during the communal chaos surrounding Independence, for refusing to take sides based on religion.

With three cash counters, Subhan Allah Cafe on Mohammed Ali Road was the biggest Irani café in all of Bombay. “Any Irani coming to Bombay would be assured of a free meal of paya and naan there,” says Koolarzade. “Then he would be directed to someone who could employ him, find others to share a room with, etc. You could plug into the Irani network over a cup of tea.” At its counter sat Haaji Muhammed Hussain Sharifi or ‘Kaana Mughal’. A pockmarked face and lazy eye had earned him the nickname. “When Iranian dignitaries visited Mumbai, they took him to Subhan Allah for lunch so that he could feel at home. Kaana Mughal eventually had seven wives, not out of ardour. If he heard of a woman who had lost her husband and fallen upon bad times, he would send her money. He knew that if sent back to her village, she would be exploited. To stop people from gossiping, they would get married on paper.”

Most Irani men married women from within the clan in Iran, to spread wealth and opportunity amongst kin. Koolarzade remembers his visits to Taft: “I had the best poached eggs. The yolks were bright orange, and cooked in ghee made from sheep milk. They were served on hot flatbreads, also brushed with ghee. On it, you’d pour honey that came from your own hives. I stayed there for months, extending my visa every few weeks, saying I was ill. Then one evening, a Kishore Kumar song played on the radio and I cried. The next day, I booked a flight home.”

Among the other Iranis were those from Shiraz, like the actor Mumtaz Shirazi. They leaned towards education and became barristers.

“Many Zarthosti Iranis also went into theatre in the 1800s,” says Patel. “They had the stature, presence, diction [needed for dialogues in Urdu] and advertisements declared that the play had ‘Real Persian actors.’ The plots also came from old Persian epics, like Sohrab and Rustom. When films became mainstream entertainment, it was unsurprising that the Iranis shone there too. Writer, director, producer, cinematographer and film distributor Ardeshir Irani directed India’s first film with sound, Alam Ara,” says Patel. Today, we have Boman Irani, who ran a wafer business and was a photographer.

“At one time, large number of Irani cafés ran in Poona, Hyderabad, Karachi and Bombay,” says Patel. “As the Sassoons and the Wadias created ecosystems around colonial centres, there was a need for bakeries, restaurants that’s served non-vegetarian food, and helped feed the working man. There would be Irani canteens at theatres-turned-cinemas, and even at the race course. An Irani may have sat on the galla of one restaurant, but he would be a sleeping partner in 10 other restaurants. The kind of financial growth they were able to achieve in one generation, has not been replicated by the second and the third.”

As money started pouring into the Koolarzade family back in Taft, Kaukan Khanum got suspicious. “Are you running a brothel in Bambai?” she asked her sons. They laughed and explained it was a restaurant that served tea and meals. “Why? Don’t people cook in India?”

Along with the Zoroastrian Iranis, the Cheliya Muslims of Gujarat managed the HMT trade of the street economy: Hotels, again cafés serving cheap non-vegetarian fare for the working class; motor as tangawallahs and later cabbies; and tabelas for the horses. They comprise Shias, Sunnis and Ismaili Agakhanis, and soon took over the restaurant business in Western India. “They took over many Irani cafés when their original proprietors began migrating back to Iran, or to the US and Canada. Like the Iranis, they would start as managers or cashiers, and then graduate to partners. They were part of the urban migration in the 1960s, coming from around Palanpur area [Gujarat],” says Patel. “They would keep their head down and work, and pull cousins into the business as their fortune flourished. The Gujarati suffix ‘bhai’ would indicate their state of origin.” They also have decidedly Gujarati last names, such as Karadia. Cheliya-ni-dukaan was often another way of saying Irani (hotel).

Each of the communities is proud of a strong backbone of ethics. A Cheliya will not confound you with business jargon; he will bargain hard, but keep his word. Payment will be on time. “My father would always tell me,” says Koolarzade, who now runs Koolar with his elder brother Ali, “remember that if you do something wrong, people won’t say, Amir is bad. They’ll say all Iranis are bad.”

Between the Gujarati cloth merchants and banias, the Zarthoshti Iranis, Parsis and the Muslim Cheliyas, the migrants made Gujarati is as much a second language of Bombay as Marathi. The first, is undoubtedly, Bambaiyya.

This article is part of Mid-day’s Mumbai Konachi? series that looks at those who played a critical role in building Bombay.

Excellent articles! Long read, but very informative and interesting.