The memoir of a Parsi ‘Tommy’ from Navsari, Gujarat, reflects his investment in the power of the British empire but also his pride in history and myths located in the pre-Arab Persian empire, and an empathetic view of the Ottoman empire.

Article by Radhika Singha | The Wire

Nariman Merwanj Karkaria served in four theatres of World War One, wrote about his experiences for the Gujarati paper Jame Jamshed and compiled these pieces into a book titled Rangbhumi par Rakhad (1922). Murali Ranganathan is to be commended for translating this memoir into English, and placing it in the context of Gujarati travel writing. One notes, with a pang, that he had to excise two forewords, a note from the publisher, the photographs, and a list of those who subscribed towards the publication of the Gujarati edition.

Karkaria begins with an account of his hell-raising childhood, and the restive spirit which propelled him away from life as a Parsi priest in small-town Navsari and put him, at the age of 16, on a boat to China. A second trip to China, at the outbreak of World War One, concludes in Karkaria’s decision to go to London to enlist in a British regiment. Journeying by train across China to Siberia, Petrograd, Sweden and Norway, Karkaria takes in the sights between changes of train, confidently setting out itineraries for other would-be travellers. With his admission to the 24th Middlesex Regiment, the narrative shifts to drills, inspections and military camps. After trench warfare in the Somme, and desert and mountain service in the Sinai-Palestine theatre, Karkaria marches into Jerusalem in the ranks of Allenby’s victorious army. What follows is a chapter devoted to places of interest in this historic city, concluding with a nominal apology for diverging from his account of the campaign: “Is it proper for a soldier on the battlefield to behave like a tourist? Let’s get back to camp!”

In May 1918, Karkaria is posted to Salonika as a medical orderly and it is here that news reaches him of the Armistice. Three months later, he finds himself sailing towards Batum as part of the Army of the Black Sea, taking a troop train across the Transcaucasian mountains to Tiflis, the capital of Georgia and thence to Baku on the Caspian Sea. The sight-seer is in the ascendant now, and we get only the barest hint that war and civil war are still simmering in the Caucasus. On his way back to England to get his discharge Karkaria takes in a tour of Constantinople and is dazzled. by it. The London he returns to is a city where soldiers, once feted, are now hungry and unemployed. Nevertheless, in a change of tenor very typical of Karkaria’s style, what follows is advice to readers on how to manage an economical stay in this metropolis. The memoir concludes with his voyage back to India, on the Zeppelin, a German ship taken over by Britain, and an emotional sighting of the Taj Mahal Hotel on the foreshore of Bombay confirms he is home.

The First World War Adventures of Nariman Karkaria: A Memoir, translated by Murali Ranganathan, Harper Collins, Delhi, 2022, pp. xxv+230 (hardcover).

Ranganathan suggests that the title Rangbhumi par Rakhad can be understood as Sorties on a Stage and that Rangbhumi might be a pun on Janghbhumi, a word Karkaria often uses in the Gujarati version. The war memoir, Ranganathan points out, had hardly any presence in Indian languages, so Karkaria modelled his narrative on the Gujarati travelogue, a well-established genre to which Parsi authors had contributed handsomely. And indeed, the battle-scapes of the First World War emerge only in chapter nine, and they virtually fade out after the Armistice. The transformation charted in the book is that of a self-confessed ‘country-yokel’, comically bewildered by new contexts, turning into a seasoned sightseer, who can advise others on what they should see, and what they could miss, what class of ticket they should buy, and what prices they could expect to pay. I use the word sightseer rather than sojourner, for it is often on the strength of a quick tour in-between catching a train or embarking upon a ship, and through scenes in train-stations, and railway refreshment- rooms that Karkaria confidently pronounces on cultural and national characteristics. He spends just about one frozen night in Siberia, and yet manages both to witness a Russian wedding, and to write knowledgeably about fox-hunting.

What links Karkaria’s account of travel with that of war is the informational drive, very characteristic perhaps of Indian travelogues authored from the mid-nineteenth century. Karkaria clearly sets out not only to entertain his readers, but also to extend their knowledge of the world. What is different is that he does so not only by introducing them to historical sites, and striking landscapes made accessible by steamships and railways, but also to the new technologies of destruction being unleashed upon the world. Describing for instance an enemy aeroplane signalling his company’s position, Karkaria halts the narrative: “Before we go further…let us take a look at the role of these aeroplanes in the war.” Digressing with deliberation from accounts of military life, Karkaria expands upon the command structure of the British army, the organisation of a military camp, the nature of the new weaponry of war, and the techniques of fighting in different theatres.

Hitherto the colonial regime had sought to keep educated Indians at a distance from any engagement with military matters. Karkaria exposes his own unfamiliarity with the Indian Army, when he describes mountain warfare in Palestine without any awareness that many of these techniques had been honed on the North West Frontier of India. In World War One, the colonial government had to keep Indians interested in the fighting, in order to mobilise resources for empire. It had to show that it was in command of the new weaponry, news of whose lethalness had circulated to remote corners of India; but it had to sanitise photographic and newspaper accounts of its impact upon recruits. However, in Karkaria’s memoir, this boundary line is breached by his description of the helplessness which assailed those placed in the force-field of heavy munitions pounding the landscape, or gas-shells poisoning the air. For instance, having elaborated upon the massive 15-inch artillery guns used in the Battle of the Somme, Karkaria writes about his company’s terrifying experience of their first bombardment, their crazed speculations about where the next shell would land, and the heart-rending cries he and his partner heard from the trench behind them.

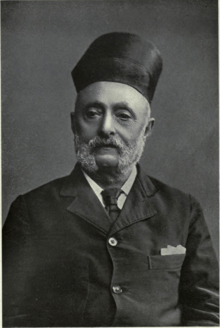

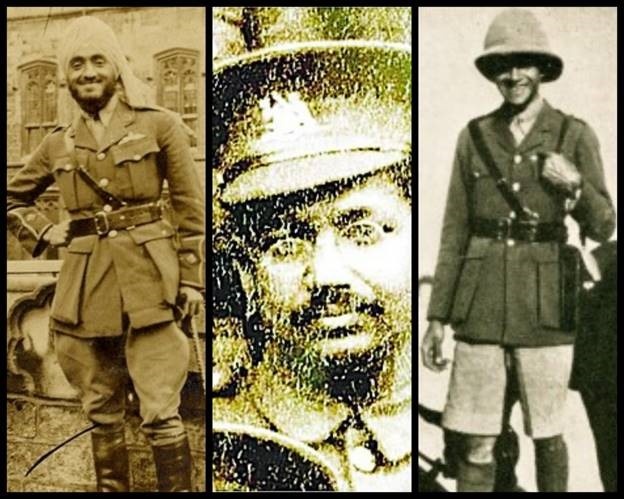

Nariman Karkaria. Photo from the book.

In his elegant and moving analysis of Indian writing on World War One, Santanu Das concludes that Karkaria’s account is perhaps the only trench narrative we have from an Indian author, and one whose realist approach is closer to the writing of European soldiers, than to the letters composed by Indian soldiers. Certainly, Karkaria would not consider that his subjectivity was similar in any way to that of the ‘illiterate’ Hindustani soldier. But both British and Indian soldiers struggled to get across to their families and to wider publics, that the industrial slaughter they were experiencing, was very different from conventional ideas about war. The fear and helplessness so often recalled by Karkaria has an affinity with the despairing eloquence with which an Indian soldier explained the irrelevance of exhortations to die bravely facing the enemy. As David Omissi records in Indian Voices of the Great War (p.110), the infantryman died in France because the ground exploded under his feet, planes dropped bombs and long-range guns massacred regiments. “(A)ny shrivelled charas-sodden fellow” firing a gun miles away could kill a score of men just sitting down to their food. “Die we must, but alas, not facing the foe!”

As with other veteran accounts, Karkaria wants the public to understand that field-service was not only about battle, but also about contending with “nature in all its fury”. Drawing upon the fact that he had survived the “killing fields of France”, he protests “the injustice done to Indian and white armies in Egypt and Mesopotamia” by the assumption that these were easier theatres. Of Salonika too, he tries to describe how, with a burnt hand he struggled to re-erect his tent in freezing winds and then gives up: “These kind of problems were an everyday occurrence…Is there any point in complaining about them now? Let’s get back on the road”.

Whether Karkaria is writing about travel or about military life, there is an intimacy of address which he uses to make his experiences knowable to a Parsi reading public. It is this public that he entertains, informs, jests with and admonishes mildly. This is where we find the emotional register of this memoir. Hindustan remains something of an abstraction, but home-sickness for Navsari can bring tears to his eyes. The date trees at Al-Arish on the coastal route along the Sinai desert remind him painfully of his “old dear town of Navsari and its palm trees and toddy.” The shops along Galata in Constantinople were “noisier than the Machhiwad fish bazaar in Navsari”. Writhing at the “ear-puncturing” sound of a Chinese musical instrument he exclaims: “Even our dear nankhatai bands are not a patch on it.” What do bands have in common with crumbly nankhatai biscuits? Dipping into www.parsicuisine.com we find that the Persian word ‘Nan’, bread, came together with Catai, Cathay, that is China, and that Parsi bakers and vendors of nankhatai, probably moonlighted as bandsmen to supplement their income. The other spaces which move Karkaria are those he associates with the sprawling Achaemenid and Sasanian empires of Iran, before the era of Arab rule opened in mid-7th C.E. This is the historical and mythic topography that Karkaria claims for himself as a Zoroastrian, one which was of increasing interest to Parsis facing the tides of political change in India.

The journey begins

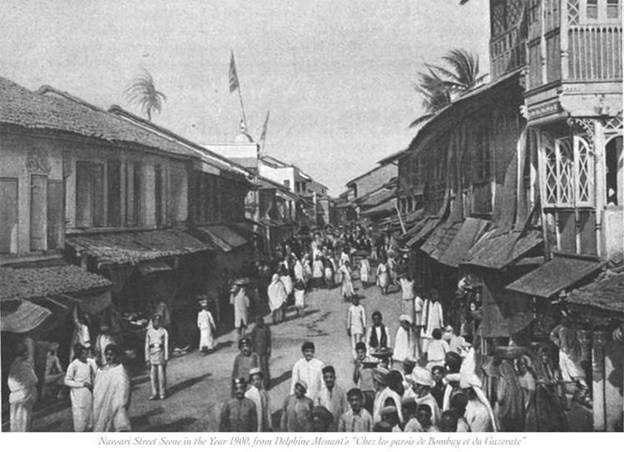

Life in Navsari is painfully provincial for Karkaria, but it is located within community networks which assist him on his travels. Karkaria was born in a Parsi priestly family, one of those clustering at Mota Falia in Navsari, a small town which can claim the oldest existing Parsi fire temple and priestly seminary outside Iran.

Navsari street scene, circa 1900. Photo: mynavsari.com

Withdrawn from school to train for priesthood, the 16-year old Karkaria decides to decamp for China. In the 19th century, the flow of opium and raw cotton from western India towards China had turned some Parsi entrepreneurs into merchant princes. Part of their wealth flowed into civic and philanthropic activity, at Bombay, in Hong Kong, and to the “uplift” of Zoroastrian communities in Yazd and Kerman in Persia. It is this network of Parsi commercial and philanthropic activity which keeps the runaway afloat on his travels.

In Bombay, Karkaria stays at the Pandey Parsi Dharamshala, In Hong Kong, he arrives sobbing at the home of Sir H. N. Moody who had made his pile from opium but shifted to banking and real estate. He is put up at the Parsi club and work is found for him as a shop assistant in a Parsi firm. When he shifts to better paid work, it is for a Parsi manager employed by a British firm in Peking, and when he sets out for London he is seen off at the station by Zoroastrian friends.

Hormusjee Naorojee Moody, Parsi businessman and philanthropist in Hong Kong. Wikimedia.

And yet we never get any sense of the emotional content of Karkaria’s relationship with those he worked for, served with, or roamed about with. As Ranganathan observes, the disconcerting aspect of this memoir, “is the complete bleaching out of individual personalities.” Was this because entertainment and instruction rather than self-revelation was the established frame of Gujarati travel writing? Or was this opaqueness the result of a desire to side-step any discussion about race distinction?

There are only two instances where we get a sense of some stress about this issue. The first is when Karkaria explains why he missed Navsari but felt restless there. One moment he is in Peking when, hearing the jingle of coins in his pockets, he finds himself back in Navsari, “walking down Mota Falia to get a drink of toddy”. Why then did he set out for China again? “I was admittedly a sahib in China, but back home I had reverted to being a black man.” Perhaps in the polyglot business world of Chinese treaty ports, where Parsi businesses co-operated with British agency houses to their mutual benefit, an English-speaking shop-assistant could feel like a gentleman.

Certainly, Parsis seem to have been freely admitted to the volunteer militia units maintained for the internal defence and coastal security of British outposts in China. When Karkaria returns to China at the outbreak of World War One, it is the sight of Parsis swaggering about in these units, which inspires him to go to London to enlist in the British Army. “My dear Parsis in Hong Kong and Shanghai”, he writes with gentle mockery, “seemed to have got into a fighting mode. They would beat their chests and proudly proclaim themselves volunteers. Someone would mention he was on guard duty the whole night… another would claim that he had to attend a parade early in the morning.,” In India, only European British subjects could join these volunteer militias, but Eurasians and the occasional Parsi were sometimes admitted. Cultural qualifications and sentiments of loyalty could open doors, and the 1914-15 crisis in France opened the doors wider.

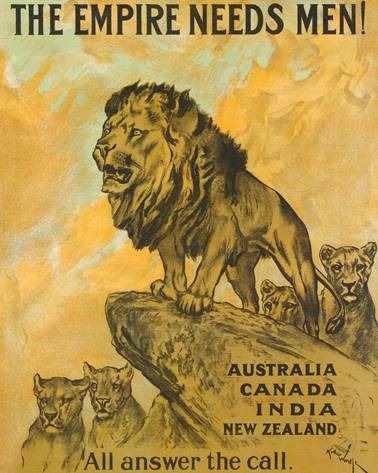

Call to (Empire’s) arms

In response to the call across empire for volunteers to join Kitchener’s New Army, business firms, educational institutions, and newspapers began to sponsor the passage of European volunteers from dependent colonies to the U.K. Mixed in with them were also “native” and “mixed-race” volunteers, who by their knowledge of English and of western ways, thought they might “fit in” with a British regiment. For Karkaria, as for many Indians at the time, the British monarch was their sovereign, and war service was expected to strengthen their claims upon empire. Yet when Karkaria jests that it was time to “ disembowel a German or two”, he was also claiming for himself the martial legacy of the Achaeamenid and Sasanian empires of Iran. Had he not read, he asks rhetorically, tales of battle in the Borzu-nama, that is, the epic poem which recounts the story of the legendary hero Borzu, the grandson of Rustam, the even more famous Persian hero.

World War One recruitment poster. PhotoL Wikimedia

How did some “coloured” volunteers like Karkaria find their way into a British regiment? Education in some mission school or college, or service in the local auxiliary militia placed individuals in networks which could facilitate this quest. Four students – three Sinhalese and one Indian, graduates of Trinity college, Kandy, an Anglican institution – were among those who set off from Ceylon in 1915-16 to enlist in England. The elite connections of some Indian families made it embarrassing to turn their sons away. Hardit Malik Singh’s tutor at Oxford University, pulled strings to get him accepted in the Royal Flying Corps. As a student at Cambridge, Kersasp “Kish” Ardeshir Naoroji, the grandson of Dadabhai Naoroji, one-time Liberal Party MP from Finsbury East, joined the Universities and Public Schools Brigade expecting to get a commission. In September 1914, he was accepted, but as a private, in the 16th Middlesex Battalion.

Murali Ranganathan suggests that this precedent might have had a role to play in Karkaria ‘s admission to the Middlesex regiment. Either Karkaria was unaware of Naoroji’s enlistment, or he wanted to claim some uniqueness for himself. We have the Northampton Mercury of February 18, 1916 interviewing a “Parsee” soldier (quite clearly, it was Karkaria), who said he had been employed by the British Government in China, and claimed “to be the only Parsee who is serving in the British home forces.” The paper described him as “a fine soldierly-looking fellow” who spoke “perfect English” and who recounted his journey from China, “by way of Siberia, through Russia Norway and Sweden to get to England”. The reason perhaps for Karkaria’s assignment to the Middlesex regiment, was that colonial volunteers coming in to London were divided up between this regiment, the Royal Fusiliers and the Coldstream Guards. Karkaria’s religion would probably have been entered as Parsi under the column heading ‘Other Protestants’. (‘Kish’ Naoroji’s own apocryphal story is that the recording sergeant refused to believe that there was any such religion as ‘Parsi’ and put him down as Roman Catholic.)

The historian Jeffrey Green refers to a file in the National Archives, U.K., titled “Treatment of coloured men in the Army” dealing with a petition to the Colonial Office submitted by six ‘coloured ‘ volunteers, admitted to the Middlesex Regiment who had been side-lined to a reserve Battalion’. They said their life at Northampton was “intolerable”, householders refused to billet them and, most damningly of all: “We are not wanted by our comrades”. One official’s peevish response was that the War Office had to rule clearly that “coloured men” were not acceptable for British regiments.

Left to right: Hardit Singh Malik, Jogen Sen, Kish Naorogi. Photos: britishlegion.org.uk, Wikimedia, soldiers.hidden-histories.org.uk

Perhaps those such as Kish Naoroji or Jogendra Sen, an engineering graduate from Leeds University, who joined the 15th West Yorkshire Regiment, could count on some local friends. Karkaria never refers directly or indirectly to any race issues in the British army. The point of interest for his readers was going to be the adventurous Zoroastrian who “turned into a Tommy”, not the slights experienced by the coloured man. (In his 1935 novel, Untouchable, Mulk Raj Anand’s protagonist, Bakha, the regimental sweeper also fantasised about turning into a Tommy). But there is an aloneness rather than loneliness which filters into the account, and might explain why friends are referenced so generically, if at all. Waking up for the first time in military camp Karkaria sits huddled in a corner, as men swear and send boots flying about the place: ‘I did not know a soul in the room; not a friend or an acquaintance … Well, I had no option but to grit my teeth and take it as it came.’ What is even more revealing, is the reason why Karkaria ranks Tiflis, the capital of Georgia, as one of the best places in Europe: “It does not matter if you are black or white or from a high or low caste. Everybody is treated just the same.”

Tiflis, now Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, in 1918, where Nariman said colour and caste did not matter. Photo: civil.ge

Karkaria shifts fluidly from “external”, rather stereotypical descriptions of “the Tommy” as that boisterous, irrepressible figure, who carries on nevertheless with the business of winning the war, to moments where he places himself in this collectivity. The most pleasurable passages are those in which he is one of a mass of marching Tommies being cheered by admiring publics in England and France. Having recovered from a battle injury in France Karkaria places himself in the “we” of the Tommy with greater confidence.

Us and them

An encounter in May 1918 with Indian soldiers on board a ship destined for Salonika allows him to flag his superior institutional position as a British soldier: “We got our food cooked by the British cooks on board, while the Indian soldiers would have to make their own rotis.” British soldiers have energy and appetite, whereas the “poor Indian soldiers could barely eat anything and just plonked themselves on the deck…. Their condition was very pitiable, but is there such a thing as pity in the army?”

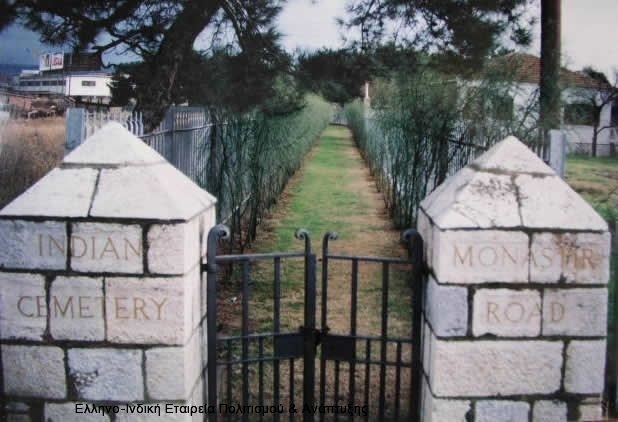

Thereafter, Indian personnel disappear from his account of Salonika. This is particularly strange, for Karkaria was posted as medical orderly in the 31st Casualty Clearing Station on Monastir road which was the forward hospital for Indian sick and wounded. Karkaria states that this hospital also had a British section, but surely his knowledge of Hindustani must have had some role to play in this posting. He gives a ghastly description of men being brought groaning, shrieking, and dying into this hospital during the September 1918 offensive against Bulgaria: “Sometimes they would have to amputate half a hand or even extract the eyeballs of an unfortunate soul.” We are left to assume that these are British soldiers, but some forty-eight Indians also died in these operations. A much larger number died of influenza and malaria.

An American Red Cross nurse, overjoyed by an invitation to visit this same hospital, said its sights and scenes had brought the pages of Kipling to life for her. For Karkaria, there was no exoticism to be milked from the presence of Muslim, Gurkha and Sikh soldiers. The quest was to engage readers in the war as it was experienced by a Parsi in a British regiment. In common with many British accounts of war service, Karkaria also dwells on a military machine that had no consideration whatsoever for the time or comfort of the ordinary soldier. It is a familiar account of endless queues, and endless inspection, of being jolted about in railway cattle-trucks, and being assigned to patrols or to fatigue duties after a hard day’s march.

Indian war cemetery, Monastir, Salonika, Greece. Photo: elinepa.org

What is different perhaps, is, that Karkaria is also fascinated by the power of the British Army, its ability to exact obedience and enforce discipline, even in the face of death. A writer who enjoyed describing how, as a child, he had set Navsari by its ears, does not offer any instance where he resisted the punishing uniformity of military routines: “You had no choice but to follow the orders verbatim.” He notes that there were men in the trenches of the Somme so paralysed by fear that they would not stir from their positions to answer the call of nature. Yet, “they were somehow drafted to do some work by the booming orders of the officers”. The Tommy might grouse and he “might exclaim about the futility of the war” but it was his discipline which ensured victory. Karkaria also marvels at the way in which the infrastructural might of the army could dramatically transform some location. At Al-Cantara, on the Suez, once the site of a few rag-tag tents, “a city had bloomed in the sandy desert.” The British occupation of Jerusalem had resulted in an excellent train service from Alexandria to Jerusalem.

Comparing China, England and India

For Karkaria, nations which were not advanced enough technologically and militarily could not hope to stand on the same footing as those who were. And for Karkaria, the travel writer, railway services were a key index of national standing. Chinese trains are denounced, and the comfort of Japanese ones produces a clumsy compliment: “The entire intelligence of the short statured Japanese seems to be concentrated in their heads.” Second-class rail carriages in England were good enough for a king. “Where will you, my dear proud Hindustan, attain these levels.”

Interestingly, in describing the backwardness of China, Karkaria has to correct Parsi ladies who thought that China was an advanced nation because of the quality of its cloth. It is a statement unconsciously but beautifully revelatory of the way in which the China connection was literally woven into the fabric of Parsi life in the form of the embroidered cloth, gara, used for caps, jackets and sari borders.

Karkaria says that these ladies did not know the current situation of China where education was in short supply. His own account of China conforms to every possible stereotype. Readers are invited to share a shudder or two about Chinese dishes such as frogs and dried rats, and about the horrors of foot-binding. He notes the irony of China having to pay for the armed units kept by foreign legations in Peking. But there is an acceptance of the inevitability of this situation, which stands in sharp contrast to a travelogue published much earlier in 1902 by a Rajput soldier, Gadadhar Singh, who came with the Indian Expeditionary force sent to quell the Boxer uprising. There is a sharp regret here about the violence and plunder unleashed on China, and the possibility that another Asian civilisation might come under foreign rule.

Yet, there are subtle limits to Karkaria’s admiration for the British empire. Firstly, there is no denunciation of the enemy side in the war. He praises German bravery in China in the 1914 siege of Tsingtao, and in Europe, and he admires the superiority of German guns, back-packs and gas masks. Turkish professional soldiers were courageous fighters and their “handsome faces” and “smart uniforms” make him feel that Turks were very different from Muslims of Hindustan. One notes again, Karkaria’s experiential distance from the Indian Army, one-third of which was made up of Muslims.

Taking pride in ‘his’ past

There are also interesting inflections to Karkaria’s description of the Dardanelles and of Constantinople. At this point in July 1919, the Allied forces had divided the city into zones of occupation. Under British pressure, the Sultan had ordered the court-martial of the leaders of the nationalist Committee of Union and Progress for war crimes, notably, the Armenian massacres. In Karkaria’s description of the Dardanelles, one detects a hint of satisfaction that this passage-way to Constantinople was not conquered during the war. How could the Turks give up these mountain fortifications from which springs flowed down like nectar? There is a delicate empathy here with the Turkish rather than Allied perspective on the Gallipoli campaign. There is also something very pointed about Karkaria’s ecstatic account of the glories of Constantinople under the “magnificent Islamic country of Turkey.” The attractions of Vilayet, Britain, would pale in comparison to the Bosphorus strait. There were wonderful things to be seen in the continent of Asia, but: “We live in a godforsaken corner of the world. How are we to imagine the strange and mysterious things that exist elsewhere.”

This rush of feeling owed something to another empire, whose past hovers over Karkaria’s memoir, and this is the sprawling pre-Arab Persian empire of Achaemenid and Sasanian rulers. Seeing the sights in Constantinople, he reminds his readers that this was a city once in the possession of Darius, third king of the Achaemenid empire. It is this mythic and historic past which provides the epiphanic moment of Karkaria’s war service. Marching into Jerusalem in the ranks of “the victorious army of our King”, he describes his state of exultation:

“While all the Tommies were excited by this new experience, my heart leapt with joy. It was this very city which had been conquered by the ancient Persian emperors, and I was following in their footsteps. Here I was a Zoroastrian soldier with a gun hoisted on my shoulder, entering the city over which flew the flag of the great British sovereign…. This was the holy land that was conquered by the famous Persian emperor, Khusro Pervez, in 614, who opened…an account for Parsis in this city.”

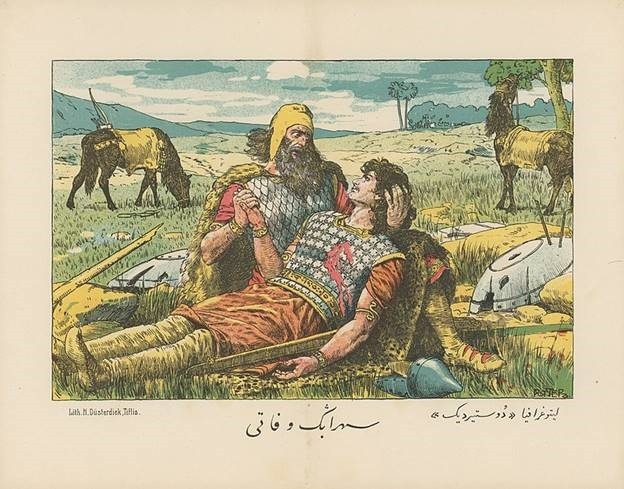

Some British soldier might fancy that he was liberating the holy land from the Saracens. For Karkaria, Jerusalem was that site which the mighty Sasanian ruler Khusrau II (590-628) had wrested from the Byzantine emperor. He is one of the heroes celebrated in Firdausi’s Shahnamah, that Persian epic which had such a hold over Karkaria’s imagination.

The Death of Sohrab by Joseph Rotter. Wikimedia.

Discerning this Zoroastrian imperial past in the territories of the Ottoman empire was an interest Karkaria expected his readers to share – since from the mid-19th century, Parsi drama companies had been staging adaptations from the Shahnamah, and over the period 1914-18, a 10-volume translation into Gujarati verse had been published. However, he also dismisses decisively the belief of many Parsis that an atashbehram – the holiest of Zoroastrian holy fires – continued to burn at the fire-temple at Surakhani, near Baku. He said the temple had been abandoned in 1880 and all he could see were stray dogs and rubble.

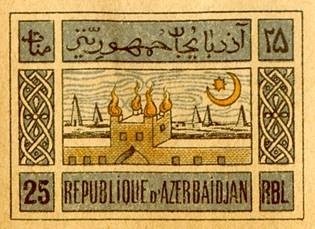

Fire temple show in Azerbaijan Democratic Republic stamp, 1919.

Yet interestingly enough, the first issue of stamps released by the Republic of Azerbaijan, an entity which maintained a tenuous existence from 1918 to April 1920 when the Bolsheviks took over, used an image of this fire-temple with five oil derricks in the background.

‘Damsels flash admiring smiles’ … but beware!

Karkaria begins his book by declaring that, in writing about his life, he was not making any claims to greatness. And indeed, an appealing aspect of this memoir is that the swagger of the traveller or the soldier is always leavened by humour. With one exception, Karkaria never lays any claim to bravery. What, therefore, is the transformation which he plots over these ten years of his life? The boy taunted by ‘an English-educated girl’ for knowing nothing of the world outside Navsari, returns from his first trip to China to discover that he was now seen as a hero: “Damsels would flash admiring smiles at me.”

For Karkaria, women are among the sights which he invites his readers to share, and he makes confident pronouncements about their beauty and femininity, or their lack of it. From this self-assured position, he also warns would-be male travellers about female shop-assistants who will press over-priced goods upon them, and London girls who will send their budgetary calculations for a toss. The winter gardens of Tiflis are a wonderland of glass palaces, lights, greenery and “snow-white beauties”. But dancing too often with the same girl, leads to an expectation of marriage, and that too, marriage merely for a contracted duration. Shocked beyond measure, Karkaria concludes that it was “best for us Parsis to stay as far away as possible away from such things.”

Parsi and British women are not so markedly the object of scopic pleasure, but Karkaria feels he can admonish both. He admires British women for donning khaki and coming right up to the front as nurses and ambulance drivers. But he disapproves of those, who, having tasted the freedom of military life, are seen in post-war London, drinking beer and smoking cigarettes. Educated Parsi women, who think they are too good for domestic duties, are put in their place by holding up the example of European women who attended systematically to housework before setting off for some job.

Karkaria was publishing his recollections in 1920-21, a time of tremendous upheaval in India. A political and civic order which had rested largely on alliances between the colonial regime and Indian notables was challenged by mass movements. The picketing of liquor shops, as part of the non-co-operation movement, affected those Parsis who depended on toddy- contracting. In Bombay there was a backlash against Anglo-Indians, Jews and Parsis for not participating in the boycott of the visit of the Prince of Wales in November in 1921. Ranganathan tells us that, after Karkaria returned, he enlisted as a lieutenant in a Parsi Pioneer Battalion, one of the part-time but paid Territorial Defence units, set up by the Indian Defence Act of 1922, and designed primarily to quell internal unrest. The Parsi community recalls with pride that the two Parsi Battalions were given some of the perks enjoyed by the British Auxiliary units, which were constituted under a different act.

There is no intimation at all of post-war upheaval in this memoir. However, Karkaria’s endorsement of the technological and military powers of a victorious empire, hints at a search for stability in the midst of change, so does his periodic retreat from descriptions of beautiful women, to norms of gender decorum. Mid-way through the book, Karkaria declares that he considers himself extremely lucky that he had “managed to return alive from the killing fields of France…to share my experiences and the trauma of that stint”. This then is the key transformative experience. A rustic youth from Navsari, of modest means, but clearly with cultural capital, had seen places and gone through experiences which he could write about. This was a make-over crucially enabled by the resources of community. For it was through Parsi networks that Karkaria could move beyond the insularity of Navsari, to access new geographies, economies, social and gender relationships.

His insistence on joining a British regiment suggests that a new horizon of aspiration had emerged. Service in four theatres took him to places he could never have dreamt of seeing otherwise. But this is also a narrative in which, by only skimming the surface of relationships, Karkaria avoids assuming the position of the raced other. The zone of comfort is the bond with his Parsi readership, which allows him to weave together old and new imperial imaginaries in his mapping of the world: his investment in the power of the British empire, a pride in history and myths located in the pre-Arab Persian empire, and an empathetic view of the Ottoman empire. None of this is easily reconciled, which is what makes the account so engaging. That Karkaria found a list of subscribers for his publication also tells us about the importance of such commemorative activity for a community feeling the winds of change.

Radhika Singha is an independent scholar and author of The Coolie’s Great War: Indian Labour in a Global Conflict, 1914-1921 (Harper Collins, 2020)