Our fourth author in the Everyday Parsi 2020 series is Soonu Engineer of London, United Kingdom

Soonu writes…

As a child, Muktad filled me with wonderment. Our house, already swept and swabbed twice daily, was given an extra special sparkle and, sometimes a whitewash, in anticipation of the arrival of the heavenly souls of our ancestors. Delicious but simple food was prepared as a gesture of hospitality. The marble-and-copper prayer table in our kitchen gleamed in the flickering light of the divo, the room filled with the fragrance of fruit, fresh flowers, and the murmur of daily prayers. It was a very special homecoming, at once mysterious and exciting: I was curious what the fravashies might make of us, but I was sure that the soul of my best beloved mamaijee would not be disappointed.

While Muktad was personal and intimate, related to one’s home and family, past and present, it was simultaneously a communal, shared experience. Every house in our colony, and in all the colonies and baghs of Karachi, prepared for this special spiritual visit and our school too was spruced up for the occasion, with prayers on the last five Gatha days, in the great hall, attended by senior pupils.

As a teenager, Muktad took on an added dimension for me. I was allowed to join the adults in an early morning session of Humbandagi at Jehangir Rajkotwalla Bagh, a community hall in the centre of the city. We woke up at dawn and set off around 6.00 in the morning, in cars and ghoragaris, on cycles, scooters, motor bikes and on foot. There was hardly any traffic on the roads as though it was specially cleared for Parsis to make their way, from all directions, to this central space. This exclusive journey, through the cool morning air of a hushed city, was exhilarating in itself. This too is part of my memory of Muktad.

Humbandagi prayers are not peculiar to Karachi but the particular format introduced by our High Priest, Shams ul-Ulema, Dr Maneckji Nusservanji Dhalla, involved congregational singing and a sermon, which was unique within the tradition of Humbandagi. We assembled, not in the Dar-i-Mehr, but in a much larger community hall. Everyone performed their Kasti prayers individually in nearby rooms and then gathered in the hall to sing together verses based on the Gathas (but reworded using the later Avesta). Several hundred people attended daily. The occasion was so popular that the congregation spilled over into the compound outside.

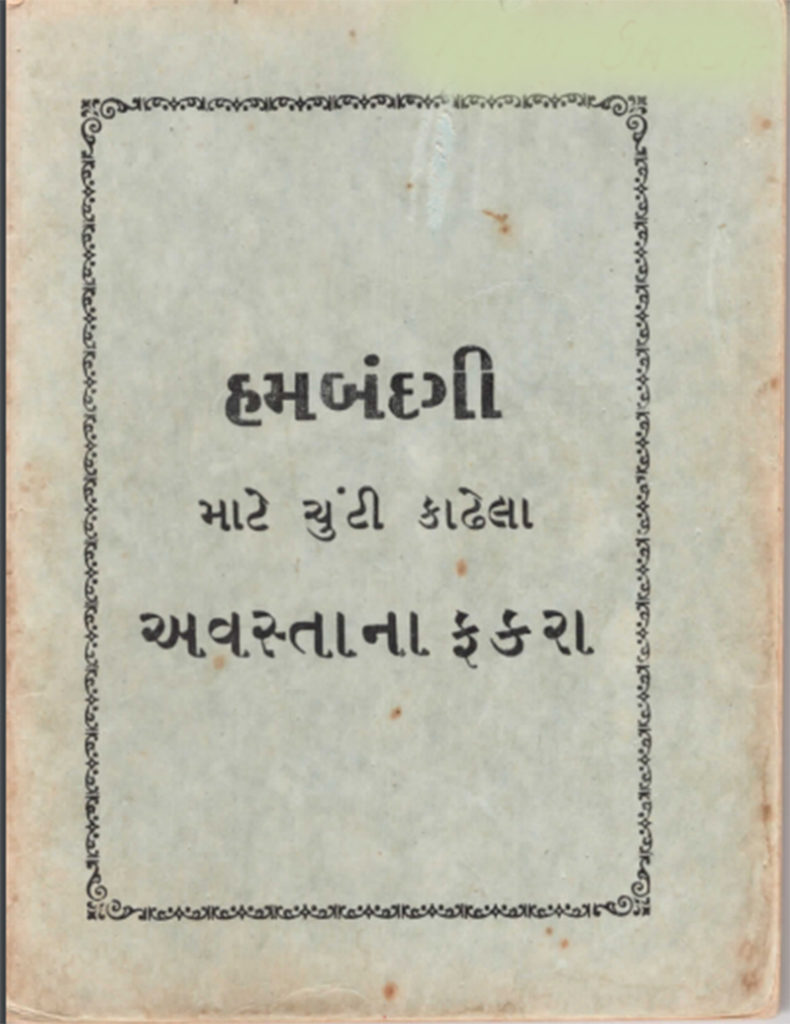

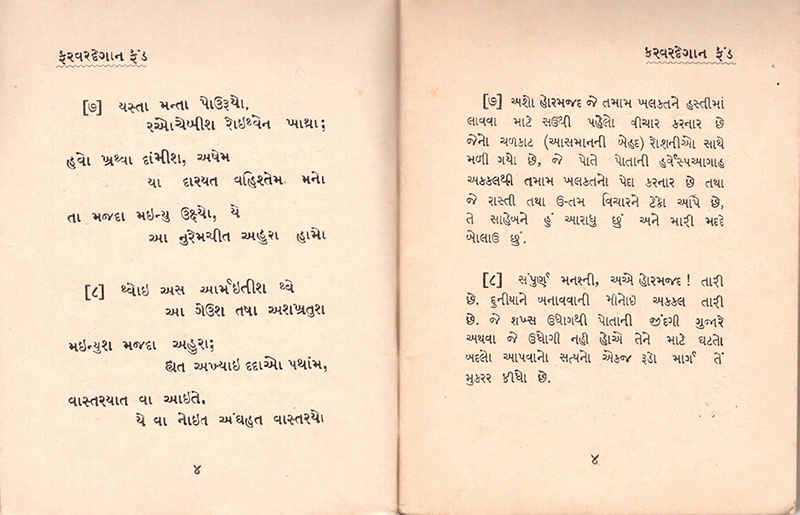

Everyone had a little pocket-sized Gujarati booklet entitled, ‘Hambandagi matay chutee kadhela Avesta na fakra’, in which the Avestan Gatha verses were published along with their translation into Gujarati. According to the booklet, the verses were compiled by Pirojshah Hormusji Dastur – Meherjirana, a practicing priest, the editor of the weekly newspaper, Parsi Sansar anay Lok Sevak, and a learned Avestan scholar himself. He had printed and donated 1500 copies to the community in March 1958.

In the Gujarati preface, Dastur Meherjirana advised, “Humbandagi means to pray together to God – that is the best prayer. It is good to understand what you pray. If you pray with devotion, it has wonderful effects on the body and mind. Praying these selected verses together, with devotion, and meditating on them, will give you mental satisfaction and peace and will surely draw you towards the divine path of righteousness.”

The Humbandagi was led by Ms Nargis Dubash. She sang each selected verse first and then it was sung by the congregation, her voice rising above theirs. I remember the melody and can hear her beautiful voice ring out, followed by the rich, soaring cadence of the devotees. Perhaps three or four verses were sung, each followed by a translation in Gujarati which was read by Ms Dubash. She would stand on a raised dais, a slim pleasant looking woman, dressed in a plain sari with a saur modestly covering her head – the model of a pious Parsi woman.

The Humbandagi was followed by a short lecture from Dr Dhalla on a theme picked out from the verses sung that morning. It seemed the community was hungry for religious information, knowledge and spiritual guidance. There was pin drop silence as he spoke. People flocked to hear him. They were as eager to hear his sermons as they were to take part in the singing of the Gathas.

We girls, mainly from the Mama Parsi School, sat at the back of the hall, in our white school uniform, our heads covered with a white crocheted cap or red velvet topee. In another corner at the back, were the boys of the Bai Virbaiji Soparivala Parsi School (BVS) also in their uniform and respective ‘house’ caps. There was as much attention paid, by each youthful group, to one another as to the hymns and sermon! This too was part of the excitement of Humbandagi during Muktad in Karachi.

By 7.30am we began making our way to school, office, or back to the home. Some people went to the Saddar Agyari or to the one at Gari Khata to pray and light a divo for their dear departed. They took fresh flowers to put in their family’s karasya. I had the opportunity, once, to visit the Saddar Agyari after Hambandagi and before going to school. I first did my kasti as normal and, instead of going to the main prayer hall, went upstairs to where the Muktad tables were laid out. The sight was breathtakingly beautiful. The long, rectangular, whitewashed hall was filled with the scent of jasmine and roses, the morning sun and the shimmering divas lighting up the silver and copper karasyas arranged on row upon row of white marble. Each karasya was in the memory of someone departed. There was no ornamentation – just the marble tables, the vases, flowers and light. That is what I see in my mind’s eye when I think of Muktad.

Muktad encouraged respect for and gratitude towards elders; concern and care for the souls of the departed and for the wellbeing of our own souls; cleanliness and care of the environment; celebration of Nature’s beauty with flowers, and of its abundance, with fruit; nourishment of the body as well as the soul; hospitality, generosity, and spiritual devotion. Spiritual cleansing during the last 10 days of the year prepared the individual and the community to begin the new year refreshed.

Decades later, I read about the theology of Muktad. It seems that our beliefs and practices in the days of Farvardegan were a harmonious blend of family-centred hospitality and devotion, with the communal prayer for all souls. To this blend Dr Dhalla contributed a particular devotional event that was, as far as I know, unique to the Parsis of Karachi.

This year, in keeping with the innovative spirit of Karachi Parsis, I am told that the Hambandagi will be conducted via ‘Zoom’ due to restrictions on collective worship during the pandemic. The verses to be sung will be emailed for each day. I wonder if they will use the 70-year-old Hambandagi booklet compiled by our ancestors.

Soonu Engineer is based in London. She volunteers for the Zoroastrian senior citizen’s befriending project and is a campaigner against the creeping privatisation of the National Health Service.