With fewer than 55,000 individuals in India, Parsi Zoroastrians have carved a niche for themselves in the country. From leading industrialists like Ratan Tata and Godrej to an army of talented Bollywood actors, prodigal Parsis are an asset to India’s culture and economy.

Article by Dr. Shernaz Cama | Edited by Jyoti Boken | Socio Martini

While their lip-smacking food, unusual last names, stellar Bollywood movies, acting skills and the sweet mention of ‘dikra’ (well-behaved boy) are a part of India’s popular culture, their expertise and contribution to the fashion world is lesser-known.

More specifically, the art of Parsi Embroidery.

Dr Shernaz Cama, a Parsi Zoroastrian and the Director of the UNESCO Parzor Project for the Preservation and Promotion of Parsi Zoroastrian Culture and Heritage shares the vibrant history of Parsi embroidery.

Textiles are a powerful medium of identity both inside and outside the culture which produces it. What Parsi Zoroastrians have saved in their cupboard and trunks is the proof of global, multicultural history.

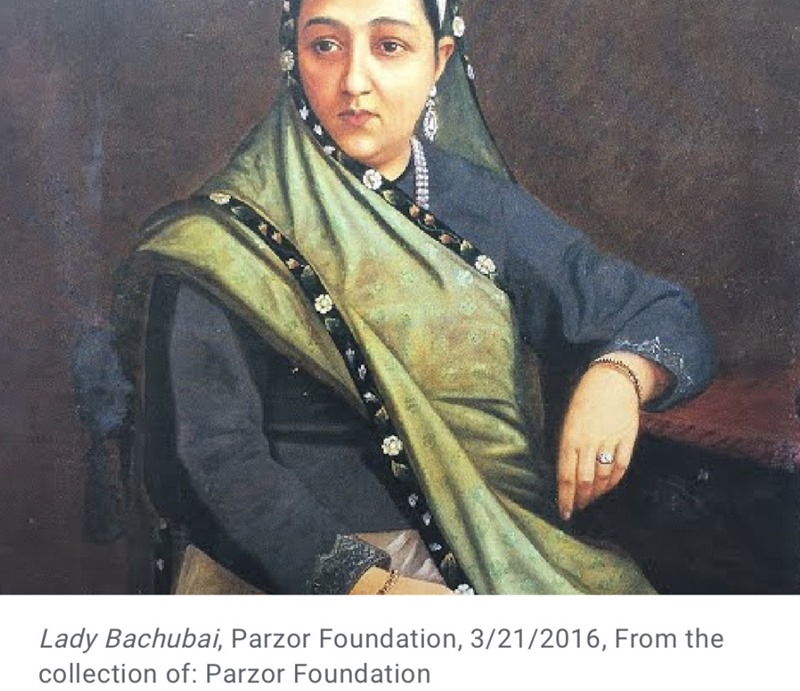

The Parsis or ‘people from Pars or Fars’, in Persia, mingled unobtrusively. One of the conditions of their refuge was that they would adopt Indian costume and language. Yet, they managed to create a distinct identity for themselves. Textiles is one of the key markers of cultural identity that contributed greatly in this aspect.

Complex roots and routes lie behind what we call ‘Parsi Embroidery’ today. The tradition grew from Achaemenian Iran, through the Silk Route into China and then came with Indian and European influences back to its originators, the Parsi Zoroastrians in India.

This engagement photograph from 1920 shows the gara sari worn in a distinct style, with a lace blouse over the sudreh or sacred garment worn by all Zoroastrians. The leather heel shoes, stockings and cummerbund show the Western influence which reinforces Parsi identity. Parsi women sure know how to stay trendy! © Parzor Archives

Fifty years ago, most Parsi homes had an embroidery cupboard with amazing varieties of shaded and coloured embroidery thread. Here, pressed into brown paper folders were butter paper patterns, home drawn with hand-written instructions about colour preferences, or initials and dates to indicate for whom and on what occasion the pattern or khakha had been created.

Embroidery has always been a vital part of the Zoroastrian love of life and appreciation of beauty and skill. The reverence for nature is interwoven and embroidered into the costumes of daily life.

A red engagement gara with the Gul-e-bulbul design celebrates life. © Parzor Archives.

The traditional embroidery celebrates the animal kingdom and bounty of nature. It is full of motifs of flowers and gardens, birds and beauty. This ‘Spenta’ or ‘bountiful’ world is to be treated with care, each tiny butterfly a manifestation of God’s Goodness.

In the Zoroastrian homeland of Iran, the Ijar or trousers were accompanied by a long jhabla which reached the knees. The head was covered with a shawl and the entire costume embroidered with rustic, simple embroidery. Fish and bird motifs prevailed as did flowers, roundels like emblems of Khurshid or the sun, tiny birds and animals.

However, after Zoroastrians were conquered people, they were forbidden from wearing bright colours as yardage. Their head dress became dark, navy or black, yet their love of life continued to be expressed in their embroidery.

A 19th Century Wedding Shawl collected from Iran and carefully preserved. Here, in this wedding costume we see peacocks, exotic colourful creatures, embroidered onto a traditional wedding shawl with the sacred Ariz, orfish, emblems of fertility. The dog, also sacred to Zoroastrians can be seen.

© Parzor Archives.

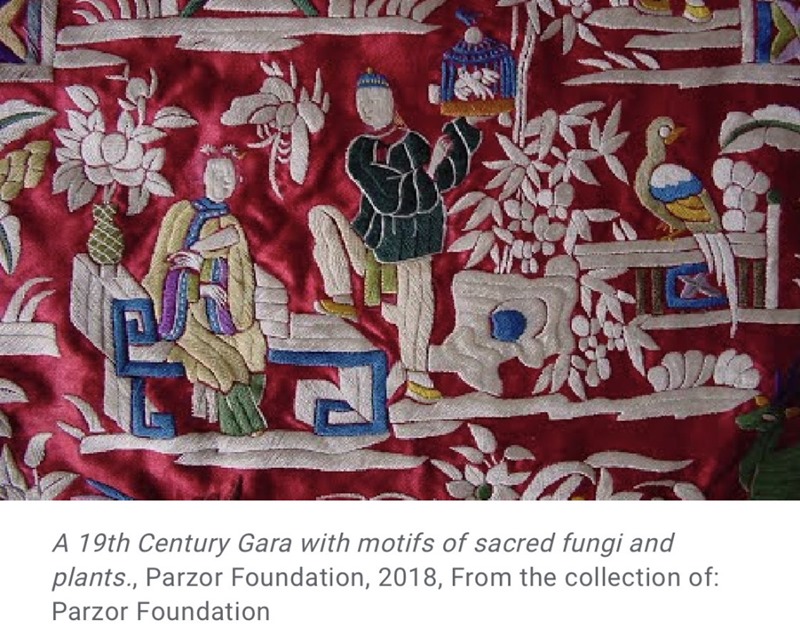

The traditional Parsi embroidery with flowers, birds and animals is emblematic of power, protection and purity. The simurgh and rooster,-sacred birds give health and protection. In its long history, Chinese symbols entered these textiles and gave to them the ‘Divine Fungus’ which like the Turkish emblem removes the ‘evil eye’.

Jhablas or tunics were worn particularly by children. The bright red jhabla combines two protective symbols: the rooster and the Chinese Divine Fungus, while this archival photo shows roosters and butterflies, symbols of protection and love for a child. © Parzor Archives.

This child’s Jhabla or tunic has roosters embroidered on the border. © Parzor Archives

This Jhabla or tunic has an inter-crossing simurgh, the Persian bird of blessing as its pattern. It is richly embroidered and includes peacocks from the Indian tradition, along with floral designs from Persia. © Parzor Archives.

In Zoroastrianism, each day is dedicated to an angel, symbolized by a flower. So the red 100 petalled rose stands for Din – Angel of Religion, the Marigold for Atar – Angel of Fire, the white Jasmine for Vohu Manah, The Good Mind.

Ava Yazata, Angel of Water, is depicted in this Parsi kor or saree border with the Water Lily, her representative flower. © Parzor Archives.

It was in the Tang and Song dynasties that this Persian love of nature, mingled with the skill of the embroidery schools of China across the Silk Route.

In this early stage of intercultural amalgam, the Khakho or seed pearl stitch developed, which has minute work like the Pekin knot. This khakho or ‘forbidden stitch, is a lost stitch, no longer practised. It did result in women losing their eyesight and hence its name.

This Khakho stitch kor (border) was embroidered by Gulan Billimoria in the 1960s. She did beautiful embroidery but lost her eye-sight towards the end of her life. © Parzor Archives.

The China connection with Persia was an overland trade link; this would change into a sea trade link with the later Indian Parsis. The first Parsi set sail for China in 1756. For almost 200 years, Parsi traders prospered, trading at Canton, Macao, Hong Kong and Shanghai.

The Chinese had begun exporting their superb embroidery to Europe as early as the 13th century AD. Legend has it that a Parsi trader in Canton, watching craftsmen embroider a rich textile, requested them to embroider 6 yards of silk as a sari for his wife in India.

These pieces often carried Taoist and Buddhist symbolism of protection such as the Divine Fungus, because embroidery in China was sacred art.

The late Mrs. Bhicoo Manekshaw of Delhi was the owner of this gara, made for an engagement in her family in the late 19th Century. It includes motifs of the Divine Fungus and plants which symbolize fertility, as well as scenes of lovers. The red colour was used for engagement garas following Indian tradition. © Parzor Archives.

In this early stage of development, embroidered yardage was covered on all four sides as if bordered within a frame. This yardage is called gala in Gujarati and its enclosed patterned space gave its name to the Gara. Parsis women following Indian tradition began designing kors or borders to match the inner embroidery, then frontage or the pallav designed to highlight the design and soon Chinese yardage had developed into the Parsi Gara sari.

Ashdeen the Designer House has re-created this complete China Chini or Chinese style gara.© ASHDEEN

The colours favoured in the Persian tradition were imperial purple and other dark shades. As Indian influence developed, the auspicious Indian Kunku red or vermillion became a favourite, particularly for engagement saris. In India, there began a tradition of using red for the engagement saree.

Indian Peacocks combine with Persian trellis and flowers, joined with the Endless Knot, to create a combination of auspicious symbols for this engagement Gara. © Parzor Archives.

This vermillion engagement gara is an amalgamation of traditional Persian trellis patters, the flowers and birds with the endless knot from the Chinese cultural vocabulary.

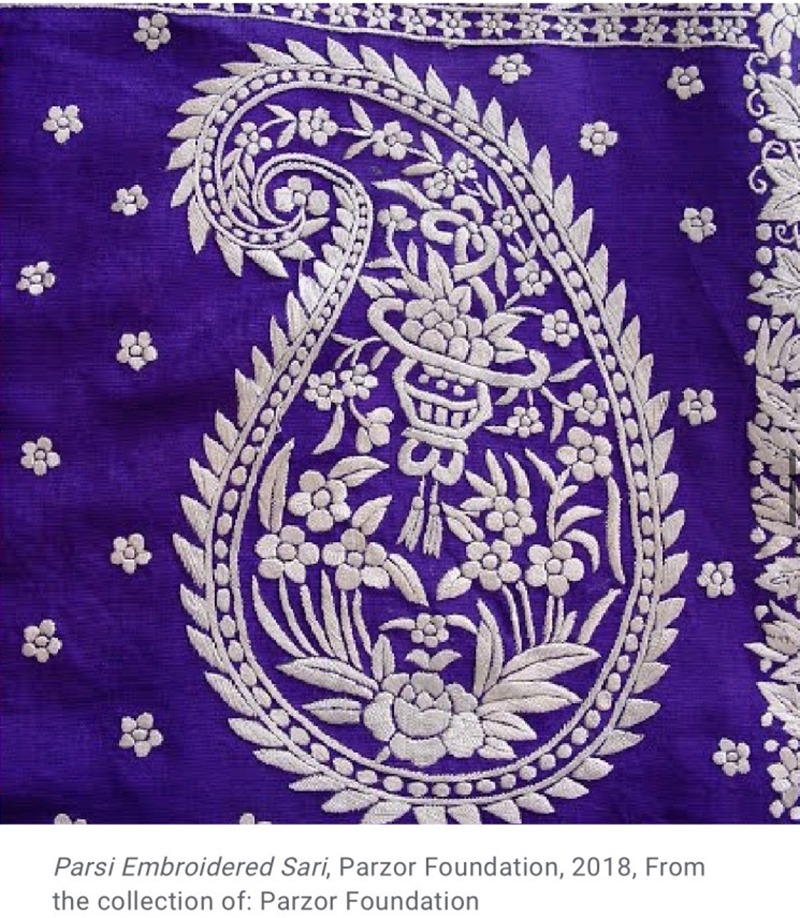

Intercultural amalgam continued. The Indian Ambi and Persian Cypress combined to create powerful motifs for pallavs, which included Chinese baskets symbolizing plenty, within their space.

The Imperial presence of Europe brought the introduction of scallops, bows and ribbons and thus four cultures (Indian, Persian, Chinese and European) came together in the Parsi saree.

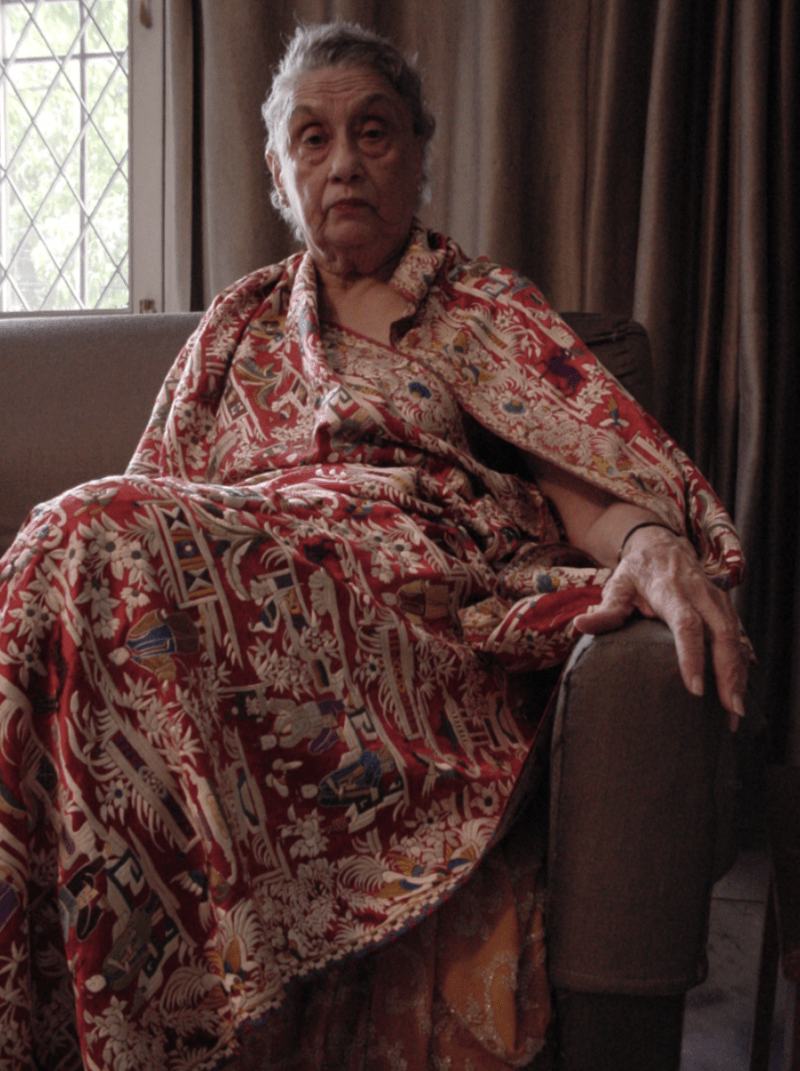

Until the early 1960s, Chinese ‘Pherawallas’ or textile vendors, came regularly in the winter season to family homes across Gujarat, the Deccan, Bombay as well as Calcutta, wherever Parsi settlements were found. Parsis favoured silk rather than cotton because it could take the heavy weight of embroidery. So the Chinese traders came primarily to Parsi homes.

Several elders across Gujarat, recall Chinese men on bicycles who sold garas by the weight. The heavier garas, with more embroidery, were more expensive. Over the years, a close relationship developed with their clients. The Chinese would leave their heavy bundles on a particular veranda during their visits. In the heat of the afternoon, they rested on the otla, veranda, and dozed. While waiting for the cool of the evening they would take out little embroidery rings to begin work. Parsis women, after completing the day’s chores, would come out on the otla to watch the embroidery with interest. So, Chinese peddlers taught Parsis women certain stitches and motifs. The women added their own myths, sacred symbols and the aari and mochi stitch which they learnt from their Gujarati women friends. In the Deccan, Deccani Zari work began appearing on Parsi Jhablas and children’s prayer caps or topis.

Little Tushna of Hyderabad models only a topi. © Parzor Archives.

It was in this way that Chinese embroidery became part of Parsi craft. With education and the freedom Parsi women enjoyed, they created businesses or professions for themselves. As times changed and with the movement of the Parsis away from Gujarat into small apartments in urban centres, a way of life was lost. The large embroidery cupboards neither fitted into the flats of Bombay nor could they be carried when Parsis migrated abroad. All that remained were the products – the garas, jhablas, ijars which carried the memory of people and their culture.

Parzor Crafts began a revival movement by teaching Parsi embroidery with the help of the Textile Ministry at Workshops across India, giving a new vocabulary to skilled Indian craftspersons.

© Parzor Archives

Now, there are modern interpretations as well. Here is an Ashdeen saree – using the traditional motifs onto a modern silhouette.

House of Ashdeen, inspired by an original Japanese kimono, this contemporary saree uses dramatic colours and combination of styles of the original garas to make a work of art. Cranes in Eastern tradition symbolize longevity. © ASHDEEN

The Parzor Seminar & exhibition at NCPA, Mumbai, 2006 brought treasures out of storage and into public notice. © Parzor Archives.

This was the beginning of a movement beyond just one community. Today, Ashdeen– the Design House has introduced this genre to celebrities like Oprah Winfrey, among others. Catering to a new market, Parzor Crafts and Ashdeen create stoles, scarves, bags and potlis as well as wedding lehangas and Western dresses.

Thus an ancient multicultural craft has become a global treasure of hand-embroidered skill; rich in its symbols and an heirloom to cherish.

© ASHDEEN

Acknowledgments:

The author wishes to thank the publishers of Peonies & Pagodas: Embroidered Parsi Textiles from the TAPI Collection, 2010. This article is based on my article “The Embroidery Cupboard: Oral Accounts of Parsi Embroidery”, in the above-named book. All interviews have been conducted during Oral Tradition Recordings across India, China, and Iran by researchers from the UNESCO Parzor Project. This article on embroidery draws upon Parzor oral heritage recordings over the past 10 years. These and the photographs are the copyright of UNESCO Parzor.

To get in touch with the Parzor Foundation, please contact [email protected] / [email protected]