The acclaimed chef and owner of Houston’s go-to Indo-Pak restaurant is putting retirement on the backburner.

Kaiser Lashkari’s name for his Hillcroft Avenue restaurant was absolutely a choice. Himalaya brazenly evokes the 1,500-mile-long range of mountains that stretch across South Asia. “The height of taste,” as Lashkari would say.

Himalaya’s heights seem as tall as those mountains: a James Beard Foundation award semifinalist nomination, a feature on Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown and multiple placements on Houston Chronicle food critic Alison Cook’s Top 100 list. But as the Indo-Pak restaurant celebrates 20 years, the summits feel secondary to the climb, especially as Lashkari attempts to launch a culinary school that will take him away from his renowned establishment.

By John-Henry Perera | Houston Chronicle

Himalaya restaurant chef-owner Kaiser Lashkari in 2017. Lashkari is one of the Houston food scene’s most notable chefs.

Michael Ciaglo, Staff / Houston Chronicle

Himalaya: An odyssey beyond 20 years

Lashkari immigrated to the U.S. from Karachi, Pakistan, more than four decades ago. Hailing from a lower-middle-class family, his parents had hoped he would become a doctor. But then he got bit by the culinary bug.

“I was two years short of being a medical doctor when I told my parents my passion was cooking,” Lashkari said. “They thought I had gone crazy because in the early ’80s, anyone who went to medical school had the best marriage prospects. My parents said I was throwing away my life.”

Undeterred, Lashkari went to the University of Kansas before he was finally accepted into the University of Houston’s Hilton College of Hotel and Restaurant Management. His early college days were marked by culture shock, as like other South Asian children, Lashkari was taught British English, which often caused consternation when he took American English classes. Dinners at home would often be had between 8 p.m. and 11 p.m., a radical difference from the usual meal times in the U.S. that normally start two to three hours earlier.

On top of that, Lashkari freely admitted he was poor when he arrived to the U.S. Even with the money from all the scholarships, he found himself borrowing regularly from relatives living nearby.

There was still some levity to be found: His classmates called him “Midas” because he was able to get free snacks from the vending machines at the dormitory. (Lashkari insists it was just a strange coincidence.)

Lashkari’s studies and on-campus work later led to jobs with Marriott, Westin and Hilton, largely in employment management and development. While the money was good, his interests still remained in the kitchen.

“You become a clone, and they want you to be a clone, and there was so much creativity in me that I didn’t want to be a clone,” Lashkari said. “In the back of my mind, I wanted to create dishes and express myself through cooking. I thought to open my own place and introduce my food to America.”

In 1992, Lashkari opened his first restaurant, Kaiser’s Restaurant, on the corner of Beechnut and Kirkwood, right in the center of Alief. He remained there for 12 years in spite of the restaurant’s small dining room of eight to 10 seats, and an uncooperative neighboring bar. Things at the proto-Himalaya looked bleak until he finally met his wife Azra on a chance encounter.

Lashkari calls Azra the “51 to my 49 percent.” When they met, Lashkari was recording a radio bit for his business, while Azra was visiting from California and sitting in at the station, a friend of one of the radio hosts.

“She heard me and thought, ‘I like this man’s voice and he appears to be as crazy as I am,’” he recalled.

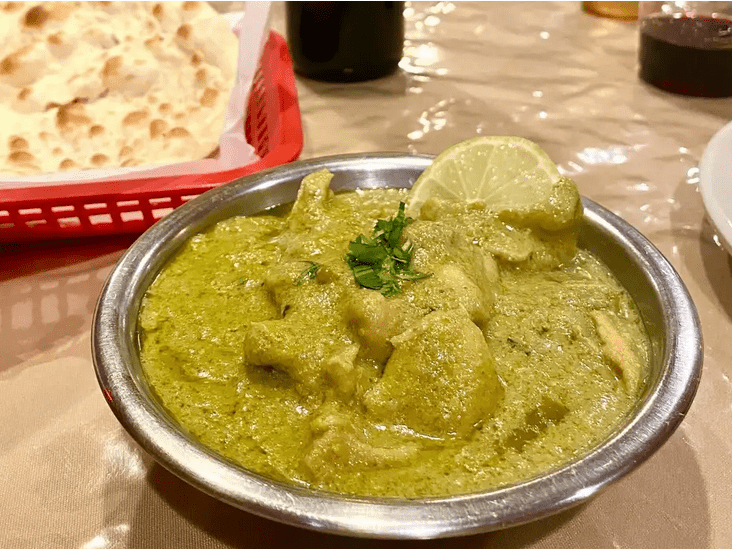

She eventually married him and the business, challenging the chef to rethink what he was doing. That includes Lashkari’s most famous dish: chicken hara masala, highlighted by a spicy green curry that offered a tang and approachable heat that other chicken dishes did not. Lashkari says Azra harped on previous versions of the dish, challenging her husband to make it sharper.

In 2004, the couple moved the restaurant to a shopping complex off Hillcroft and the Southwest Freeway. After the name change to reflect “the height of taste,” the rest was history: Himalaya became an alluring draw to Indo-Pak fans and critics from both inside and outside the city. Much of that can be attributed to Lashkari’s high standards in the kitchen and his repeated mantra, “Cooking has to be done from the heart.”

The chicken hara masala at Himalaya.

Megha McSwain

‘This is my bread and butter’

Those high standards have earned Lashkari substantial criticism from people inside the food and beverage industry, and even to regular customers. Scroll through some of the lower-starred Yelp reviews of Himalaya, and you’ll find plenty of testimonials about the “abrasive” and “rude” owner.

Lashkari was not shy to admit that he has terminated employees over the years, even publicly dressing them down in earshot of customers. In one account, a server delivered food to the wrong tables four times during a shift. The fifth time it happened, he exploded at the server inside the kitchen.

I had a good guess at what kind of man Lashkari was during our time together because I’ve met him before. He’s my father-in-law, who immigrated from Kerala, worked at an alarm company until he took ownership of it and later became a mini-real estate tycoon. He’s my uncle: a former police detective in Sri Lanka who filed for asylum in Canada and started a successful trucking company. Most immigrants who are able to carve out a slice of the Western world for themselves only have two speeds: zero or 100. Lashkari falls in the latter category, and that drive can often be interpreted by onlookers as “abrasive” and “rude” for people who aren’t in the know.

“I am what I am. I don’t hide my feelings,” said Lashkari. “Some people say, ‘He’s a Hitler in the kitchen.’ No. If I was, I wouldn’t have these 10 core people in my staff. Even as much as they wanted a job, they wouldn’t tolerate me or vice versa.”

Two decades in, Lashkari has mulled retirement: When will he do it? How will he fill the hours of the day? Will he drive Azra crazy?

It’s not a secret that Lashkari has wanted to open a culinary school. Come summer of 2024, he says, the James Beard award-nominated chef will open the Himalaya Culinary School in Sugar Land. Lashkari says it will be the first culinary school focusing on Indian and Pakistani cuisine in the U.S.

The logo for Chef Kaiser Lashkari’s Himalaya Culinary School in Sugar Land, Texas.

Himalaya/Handout

“There are certain iconic dishes in the restaurant that everyone who has eaten in Himalaya wants to duplicate in their kitchen,” Lashkari said. “They would ask, ‘Please, let me have the recipe.’ I declined because this is my bread and butter. I can’t do that until I retire.”

The school comprises two buildings and is still in the works at the Grand Parkway and Southwest Freeway. CultureMap originally reported it was going to open in February 2024 but since then, Lashkari has had to deal with continued permit difficulties. The new opening date is set for sometime in May or June.

“The class will be no more than 15 people because you lose the individuality,” Lashkari said. “And then I want to take in serious people who are serious about food. This is not going to be like a social or hobnob thing. I will teach them from the bottom of my heart.”

Lashkari will teach two days per week, Wednesday evenings and Sunday mornings. He’ll still hold court at Himalaya, but when he’s away, Azra and his sister-in-law will be running the front and back ends of the restaurant. School fees will run $50 to $60 per single class.

A significant part of the school’s purpose is to benefit a cause Lashkari has been very animated about: ending hunger. All proceeds of the Himalaya Culinary School will go toward feeding the hungry and poor. While he didn’t explicitly say who would benefit, Lashkari has worked with the Houston Food Bank and Periwinkle Foundation in years past.

“When we came here, we had nothing,” Lashkari said. “I had less than $500 in the bank as my life savings. Whatever I made here, it’s all because of the support of Houston and our customers. And the thing that made us what we are today is the food.”