Madam Cama first fluttered the Indian flag to the world in August 1907, paving the path for Bombay Presidency’s feistiest women patriots

Bhikaiji Cama, the early catalyst for free India. Pic Courtesy/Wikicommons

Article by Meher Marfatia | Mid-Day

All was far from quiet on the western front. The most pivotal freedom bids launching from the Bombay Presidency—Non-Cooperation, Home Rule, Khilafat, Khadi and Swadeshi movements—were propelled to a significant extent by women with rare courage of conviction. Not all of them are as equally chronicled for contributions that culminated in shaking off the British yoke 75 years ago.

All was far from quiet on the western front. The most pivotal freedom bids launching from the Bombay Presidency—Non-Cooperation, Home Rule, Khilafat, Khadi and Swadeshi movements—were propelled to a significant extent by women with rare courage of conviction. Not all of them are as equally chronicled for contributions that culminated in shaking off the British yoke 75 years ago.

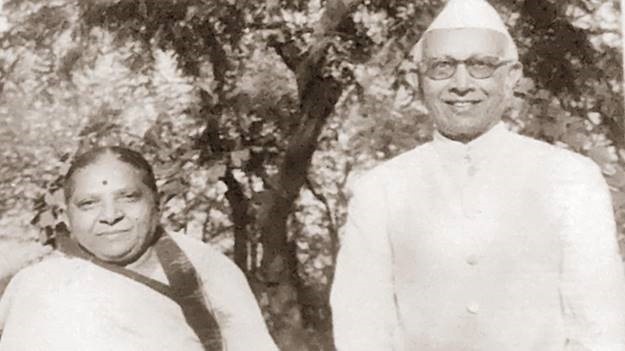

The little-known story of Vijya Parikh is worth the telling. On marrying cotton trader Durlabhji Parikh, from Limbdi (the princely Gujarat state entitled to a nine-gun salute during the Raj, reigned by a Thakore who wilily tried impressing the British by opposing the Congress), she discovered her ideals aligned firmly with those of her in-laws.

Fracturing the salt law: Satyagrahis boiling sea water to extract the taxed mineral in the Congress House compound. Pic Courtesy/Getty Images

A veritable repository of family history, octogenarian Ramesh Parikh says, “My father Durlabhji was the janata’s representative assigned to agitate outside the Limbdi palace. His brother Rasiklal Parikh became the chief minister of Saurashtra State and first home minister of separately carved Gujarat State. In Bombay, my mother Vijyaben met Dadabhai Naoroji’s granddaughters, Perin and Goshasp (Goshi) Captain, who further fuelled the revolutionary attitude already seeded deep in her.”

Kept out of activities initially—Indian leaders fearing the English might criticise them for holding women as shields for their fight—Indian women grew emboldened of their own accord, realising they could play a considerable role reshaping the country’s fate. It is acknowledged that the ladies’ freedom movement was largely the doing of women of substance such as Vijyaben Parikh and Maniba Nanavati. A good deal of plotting and planning hatched in their homes with the Mahatma’s blessings.

Vijyaben and Durlabhji Parikh. Pic Courtesy/Parikh Family

Throughout April 1930, at least 300 women enrolled for picketing, would routinely start from Congress House and proceed along Girgaum Road, Princess Street, Mangaldas Cloth Market, Mulji Jetha Cloth Market, Zaveri Bazar and Bhuleshwar. Reiterating the necessity to boycott British goods, they entreated shopkeepers along the way to deal only in swadeshi items. And pleaded with millhands—“Unless you give up liquor and not touch foreign cloth, we will have to continue our picketing demonstrations.”

Aditi Parikh, the daughter-in-law of Rameshbhai’s older brother Nalinbhai, shares interesting anecdotal memories she has heard. “My father-in-law learnt to walk in jail. Vijyaben was arrested after a protest. Gandhiji requested the sentencing judge to grant leniency as she had this toddler child. When he did not, she took my father-in-law with her to Arthur Road jail. Learning to take his baby steps there, he fell on the hard stone, but proudly bore that scar lifelong—a badge of honour to his mind.”

Mithuben Petit (centre) with Gandhiji and Sarojini Naidu. Pic courtesy/Wikipedia

Rameshbhai brings forth a framed letter written in Gujarati in which Gandhiji, incarcerated in Poona, enquired after Vijyaben’s health in Bombay. He goes on to narrate his plucky mother’s involvement with a momentous incident.

It was December 12, 1930. A poor 22-year-old farmer-turned -mill labourer took to exposing the unfair trade practices of British companies. Babu Genu and his sympathisers blocked a truck loaded with a consignment of foreign materials, close to the Parikh home in Kalbadevi. Lying prostrate on the road, he refused to let the vehicle pass. The police mowed him down. It was Vijyaben who roused onlookers paralysed with shock into arranging for Babu Genu’s body to be transported with dignity from the brutal scene.

Malatiben and Damubhai Jhaveri. Pic Courtesy/Parul Sastri

“Right after Independence, Partition refugees needed to be fed. Goshi Captain put my mother in charge of logistics for the Mulund camp. The group of ladies who were sent to jail with her were part of this operation, ensuring there were daily rice and roti rations for the displaced,” remembers Rameshbhai.

The upswing preceding the 1930s events triggering 1947 was set into motion by the early courage of Madam Cama. Backtracking some decades, we encounter an irony the British took time to swallow. Cama’s community, small yet known for loyalty to the Crown, still succeeded in stirring strong enough ferment. Not only did Parsis front the freedom struggle, among the most radical anti-Raj voices were women such as Bhikaiji Cama, the Captains and Mithuben Petit.

That Parsi women were among the country’s first to be educated was a privilege they employed to advantage and one forming the raison d’etre for their involvement with the Independence movement. They were often from households unlikely to be associated with commitment to the cause against colonialism.

From an affluent Patel family, Bhikaiji believed women joining politics would propel their emancipation. The year that excited her, because of the formation of the Indian National Congress, 1885, was when she married Rustomji Cama too. He proved a disappointingly pro-British lawyer and ideological differences drew them apart.

Travelling to Europe in 1902 to fully recover from ill health on account of the plague, she contacted empathetic compatriots. On August 22, 1907, Bhikaiji presented a strident sight at the second International Socialist Congress in Stuttgart. Saree pallu crowning her head held high, she strode on stage to unfurl a green-yellow-red striped flag, emblazoned with the words Bande Mataram, before the global gathering. And declared, with typically passionate oratory, “This flag is of India’s independence. I appeal to lovers of freedom over the world to co-operate with this flag in freeing one-fifth of the human race.”

She delivered lectures at London’s Hyde Park on famine devastation in India and on the imperative need for its autonomy, got invited by Lenin to settle in Russia, had her portrait splashed alongside Joan of Arc in French newspapers, and travelled to America and Africa with her flag. Across foreign soil, during the long exile from her homeland, she raised an incredibly high awareness of atrocities against Indians and the vital need to rally with their clamour against oppression.

Also eschewing great wealth to espouse non-violence and rural activism, Mithuben Petit was strongly influenced by the view that real India lives in her villages. She set up Stree Swarajya Sanghs where women were instigated to peacefully picket shops selling foreign cloth. Her aristocratic family members were aghast. Not objecting to Mithuben’s constructive social work as much as her sparking opposition to the English, they warned her to renounce such “ridiculous” activities or risk disinheritance. Mithuben’s cool retort to the clan struck fresh fervour among brave hearts of the day: “It is your business to sit with the government and mine to remain with the nation.”

At Sorbonne University in 1905, Perin Captain was introduced to Bhikaiji agitating for Indian liberation in Paris. The liaison developed into an infectious friendship, which goaded Perin with audacity. She burst into fiery nationalist songs at a conference in Brussels and thought nothing of defiantly visiting Veer Savarkar in jail under the assumed name of Miss Ardeshir.

On Pateti day of 1906, Perin had drawn her Oxford-educated sister’s attention to “that man with very nice eyes” at a boat party on the Thames hosted by Jamshedji Tata. That was Gandhiji in attendance. He enlisted the sisters’ support in South Africa for Indian self-rule. On his return, he held a meeting of immense consequence at the Petit ancestral home in Bombay, exhorting ordinary people to fight relentlessly for freedom as both, a birthright and undeniable duty.

Inspired, the Captains traded their luxurious silks for coarse khaddar sarees and spearheaded the propagation of ahimsa through women’s organisations such as the Rashtriya Stree Sabha and Desh Sevika Sangh. Perin galvanised her sisters in arms into expressing their displeasure to Gandhiji about merely being allowed the picketing of shops.

As the Dandi March ended on April 6, 1930, growing numbers of women joined the Salt Satyagraha, encouraged by Sarojini Naidu and Matangini Hazra. Mithuben Petit stood behind Gandhiji when he violated the Salt Law again at Bhimrad.

Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya bunched together volunteers for prabhat pheris (dawn processions) and to scoop salt and brine at Chowpatty and Juhu beaches. With a determined army of likeminded women, she headed to Chowpatty to collect sea water to be evaporated on small chulha stoves. The police arrived with rough boots and batons to beat them. Even those who began witnessing the violence as mere spectators were forced to leave the balconies from where they watched events unfold, to help the injured be carried away to hospital on makeshift stretchers cushioned with bedsheets they provided.

The air across the city was thick with cries of “Namak kaida toda hai, we have broken the salt law.” Lilavati Munshi marched groups of women to a wire barrier

near the Wadala salt depot within dangerous distance of armed Eurasian sergeants.

The Bombay Chronicle (whose first editor BG Horniman had been an azaadi supporter) reported several housewives carrying clay, brass and copper pots and pans joined the agitators. That salt was later sold outside the Bombay Stock Exchange and High Court. With characteristic insouciance, Chattopadhyaya waved a packet under the nose of a startled magistrate, asking if he would buy “the salt of freedom”. This powerful, symbolic march by Gandhiji, warming the very soul of India, presented a turning point for women to claim public space in vast numbers for the first time in the country’s history.

Explaining effectively used traditional literary metaphors, Kunjlata Shah writes in Patriotic Songs in Gujarat (1920-1947): The Gandhian Inspiration—“Folk literary forms of garbas, kirtan, garbi, katha, nurtured in Gujarat, were utilised creatively and meaningfully to mobilise women politically… In the Bardoli Satyagraha, peasant women participated in the passive resistance against British rule. Special songs, garbas, and raasdas were composed to keep their spirits and morale up.”

Recounting those cataclysmic years, pacifist writer Horace Alexander noted: “Day by day, the streets of Bombay would be livened in the early morning with the songs of freedom. Women could be found all over the city. Many had never taken part in public life before.”

Fast forward to educationist-activist Aruna Asaf Ali saluting the Tricolour at Gowalia Tank maidan, with shouts of “Quit India” renting the August 1942 air. She had participated in protests during the Salt Satyagraha. Arrested, she was not released in 1931 under the Gandhi-Irwin Pact, which stipulated letting go all political prisoners. In solidarity, the other women refused to leave the premises unless she was released. Post-1947, she remained active in politics, becoming Delhi’s first woman mayor.

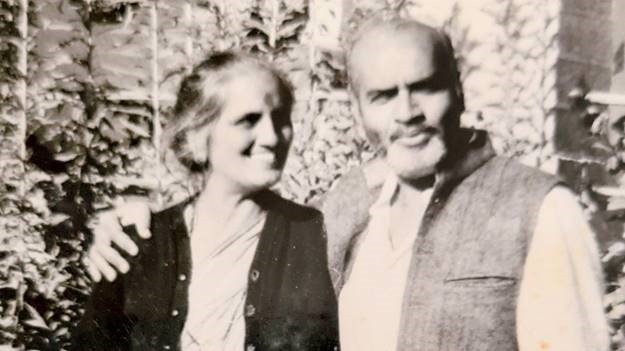

In her Babulnath apartment, adorned with images of Gandhiji and Ganesha, Malatiben Jhaveri would greet visitors at the dining table where she spent hours translating classic epics from Hindi to Gujarati. Growing up in the Nepean Sea Road mansion of her silk merchant father, Sir Shantidas Askuran, Malatiben dropped Sanskrit studies at St Xavier’s College to devotedly join the Independence struggle. On August 8, 1942, she wore the red khadi saree given to volunteers attending the explosive Congress session at the Gowalia Tank green soon to be christened August Kranti Maidan.

As Aruna Asaf Ali hoisted the Congress flag, Malatiben earned a precious personal victory. Teargas was released for the first time in India. When a piece of shell landed on her, she lobbed it right back at a British soldier. Burnt but triumphant, she was whisked off to jail, where she won even police sympathy for unstoppably singing nationalistic lyrics.

The same steadfast rootedness made Malatiben work tirelessly to promote indigenous textiles. Her sister Prabha Shah and she set up the Sohan Sahkari Sangh, a pioneering effort in the non-government sector for handlooms and handicrafts.

Malatiben’s abiding passion was theatre, which she flung herself into with uncommon energy. The constitution of the Indian National Theatre (INT) was cradled in confinement, inked by patriots such as her husband Damu Jhaveri, Chandrakant Dalal, Rohit Dave, and Mansukh Joshi. Confident that the country was on the verge of liberation, they were keen to script a unique cultural policy. On May 5, 1944 (Iqbal Day, commemorating the poet who memorably composed Saare jahaan se achha), INT was launched to nurture the regional performing arts.

Over a hot thali lunch, Malatiben had reminisced, “We were born at the right time in this country, just wanting to defy excesses of the Raj. Women like me then referred to prison as ‘saasre’—our in-law, second home.” Jailed three times in 1942 alone, she well knew the power of this truth.

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at Qmid-day.com/www.meher marfatia.com