Why have Parsi natak audiences been rejecting plays that don’t sugarcoat the pill?

What were you thinking? How can you do this? I cried in your play!” That was Hindi film character actor David Abraham chiding Adi Marzban backstage after the opening night of Asha Nirasha in 1968.

Article by Meher Marfatia | Mid-Day

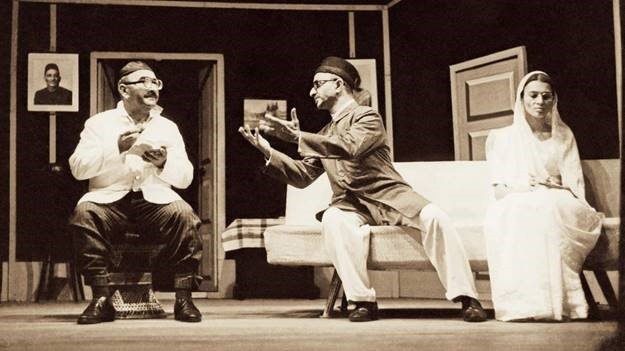

Adi Marzban (extreme left) in a rare silent cameo, the elegiac condolence meeting opening scene of Asha Nirasha. Pics/MEHER MARFATIA/LAUGHTER IN THE HOUSE: 20TH CENTURY PARSI THEATRE

Like David, thousands of theatre-goers simply could not accept the bleakness of this worthy sequel to the popular Sagan Ke Vagan. Critically hailed but commercially nixed, Asha Nirasha examined the trajectory of loneliness, loss and bereavement. No matter that cardiologist Rustom Vakil complimented Dolly Dotiwala for her completely convincing heart attack scene, the overall gravitas made the production bomb. Sensitively scripted, competently acted and meticulously rehearsed for eight months, it closed after eight shows.

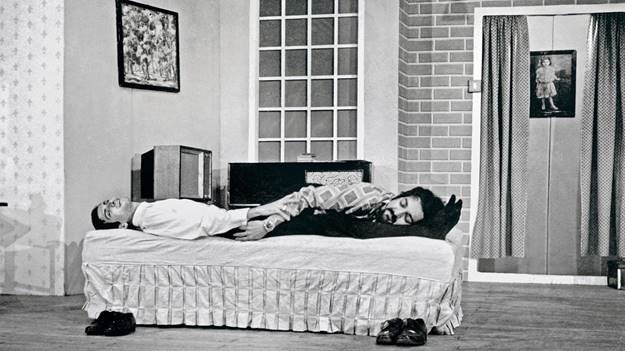

Bomsie Nicholson and Rohinton Mody in Aay Calendar Konnu

Asha Nirasha was actress Scheherazade Mody’s first play with Marzban. “He planned for it to be grimmer,” she recalls. “Even what pathos was presented didn’t go down well. Despite lighter lines, audiences saw—and rejected—the seriousness. Only one word associated with Parsi nataks stuck in a groove of their minds: comedy.”

Drama being the dominant form of entertainment in urban India from the 1860s to the 1930s, influenced by British travelling troupes, Parsi companies performed on proscenium stages decorated with heavily painted curtains which rose on declamatory acting and mechanical devices creating spectacular effects.

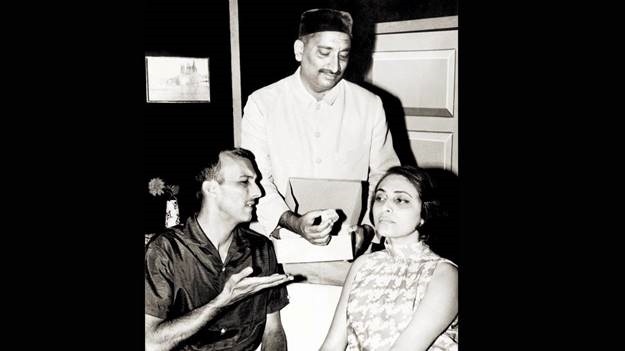

Bomi and Dolly Dotiwala with Pervez Mehta (centre) in Sagan Ke Vagan, the prequel to Asha Nirasha

This theatre took a new turn post-Independence, its standard bearers being writers of the stature of Marzban, Pheroze Antia, Dorab Mehta and Homi Tavadia. “Not a single of Pheroze’s scripts had any room for negativity,” says his actress wife Moti. “Fans said: Saara dara per aapuneh rarvu nathi, we won’t weep on festive days.”

Credited with more versatility, Marzban was challenged to switch genres or combine them. “Adi, can’t you write a thriller?” he used to be badgered. “Be the Indian Alfred Hitchcock.” Not one to refuse a challenge, he pondered over it. The result was Ardhi Raate Aafat. Reviewers lauded his masterly interspersing of scary tension with moments of mirth pulled off with panache by the cracker of a cast comprising Homi Tavadia, Dolly and Bomi Dotiwala, Ruby and Burjor Patel, Dadi Sarkari, Pervez Mehta, Jangoo Irani and Hilla Nariman. Keeping viewers spooked, Marzban dexterously changed the murderer’s identity in some shows.

Fans of the suspense saga still applaud the fear factor conveyed so effectively. Replete with spookily creaking doors, flickering bulbs and sound effects from barking dogs and howling winds, its supernatural leitmotif popped up as a hideous hand. Strong men in the audience jumped in seats they were already teetering on the edges of, when a black caped figure stuck it out from the bookcase in a creepy home.

In 1953, a UNESCO scholarship took Marzban to southern California’s Pasadena Playhouse to study theatre arts. Influenced by the humour of P G Wodehouse, James Thurber, W W Jacobs, Robert Benchley and Stephen Leacock (closer home it was Chandravadan Mehta) and eager to implement what he imbibed, his writing and direction infused realism in Parsi drama.

With Piroja Bhavan in 1954 he birthed a whole new stage lexicon. Parsi theatre finally moved from blood-and-thunder Sohrab and Rustam, Harishchandra and Shakuntala to plots tackling themes of relevance and universality, including trouble in love, marital complications, inheritance, illness and old age.

“Aay Calendar Konnu focused on a woman impregnated with donated sperm,” says Scheherazade Mody. “Bomsie Nicholson played the donor, my husband Rohinton was one of Dolly Dotiwala’s suitors.”

Realism was just about all right. Tragedy, never. Despite sensing the resistance to the infusion of deep content, Marzban attempted to address contemporary concerns sporadically. That was how Mancherji Konna was strategically set against the backdrop of Indo-China hostilities and Pakar Maru Puchhru fronted Bombay Parsi Panchayet politics.

It was not easy going against the grain. Audiences in anticipation of a rollicking evening failed to turn thoughts to opposite issues of conflict. They could not appreciate being called on to soul-search their way through a subject like euthanasia, which Marzban brought to the forefront in Jeevan Khel, his last production with Bomi and Dolly Dotiwala.

“Jeevan Khel was far ahead of its time. People could not bear dealing with this because it came from Adi,” said Dolly, who played mother to a boy battling terminal illness. Ironically, and perhaps because of his own condition, Marzban picked this play to explore possibilities. He was directing it from the confines of his bed as he coped with the ravages of lung cancer. On his passing away in February 1987, Shailesh Dave directed a few shows.

Describing the self-conscious, awkward response to sad stories, actor Dinyar Tirandaz says, “Slotting us, viewers are reluctant to see a small sub-plot that can’t always be fully funny. Faced with sombreness, people often laugh all the same. Inappropriately, nervously, but they laugh not knowing what else to do.”

Public perception presumed Marzban incapable of generating anything but laughter. So much so, that he too came to believe their assumption and justify it. In a 1971 interview to Bachi Karkaria, he said, “People don’t leave tragedy behind at home to discover it has stalked them into the auditorium. When God’s in his heaven and all’s well with the world, people can, with relieved detachment, watch tragedy. Not otherwise.”

Meherzad Patel of Silly Point Productions reasons, “The crux of the situation is that people want to laugh. Full stop. Be it for a festive occasion or on a regular day, people step out for an entire evening—the play, followed by dinner and conversation. The last thing you want is to try pushing away office pressures and domestic disputes, only to fall back into similar experiences. Comedy makes you forget problems. Online platforms take care of your emotional quotient, the chillers with murders and bloodshed. Live performances are expected to entertain, that’s all there is to it today.”

Navroz Mubarak now. With wishes for a big bellyful of corny as hell-yet spirit lifting laughs in the hall to which you’re headed.