When Delhi-based professor Shernaz Cama told the Parsis about the disgrace in which historical accounts were lying at the Meherjirana library, it became an emotional discovery for them.

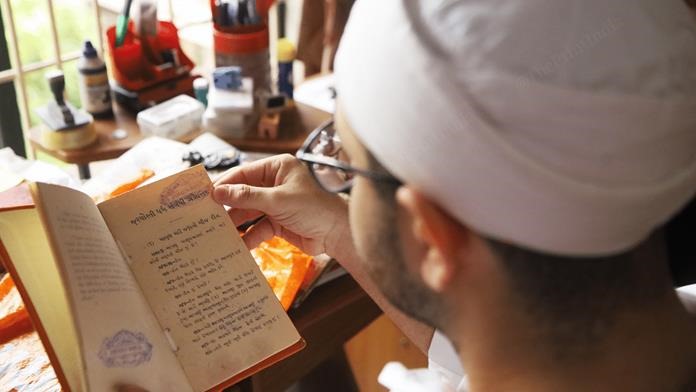

Parsis now don’t know how to read old Parsi text, including the priests. They rely on texts written in Gujarati | Manisha Mondal/ThePrint

Article by Shubhangi Misra | The PRINT

Navsari/New Delhi: There were tears in Shernaz Cama’s eyes when she stumbled upon a Parsi hidden treasure in the depths of a 120-year-old library in South Gujarat’s Navsari. What she discovered that summer of 1999 wasn’t a cache of gold or precious stones, but ancient Parsi religious texts worth more than a king’s ransom. She carefully unearthed crumbling manuscripts from dusty old wooden almirahs of First Dastoor Meherjirana Library.

“It was the history of an entire community simply vanishing,” says Cama, a professor of English at Delhi’s Lady Shri Ram College for Women and co-founder of the NGO Parzor Foundation, which works for the preservation and conservation of Parsi Zoroastrian culture and history.

The Parsi Zoroastrian handwritten manuscripts—some as old as 700 years—in Persian, Urdu, Gujarati, Avestan, Pahlavi and even Sanskrit, were rotting away in these cupboards, victims of India’s nasty habit of not preserving and archiving historical accounts.

Cama’s discovery all those years ago injected an urgency in the small close-knit community that is trying to reverse the tragedy of its slow extinction. For the Parsis, it is a crisis of memory as well as memory-keepers. The loss is at once urgent and historical. They fear that the tangible and intangible threads of their history, culture, philanthropy, and memory would vanish as well. And it has united all factions of the community–the wealthy and the not-so-rich, the young and the old, the traditionalists clinging to the ways of purity and the modernists demanding change.

It was the history of an entire community simply vanishing

– Shernaz Cama,co-founder, Parzor Foundation

From Mumbai to Hyderabad, and Navsari to Kolkata, photographers are scouring family homes across India for old artefacts, memory-objects and stories to preserve, archive and exhibit history. Researchers and conservationists are preserving parchments. Scripts of plays are being digitised, heritage bungalows and baugs are being restored and oral histories are being recorded for posterity.

Many Parsis around the country have banded together to save their collective consciousness, generously giving away family heirlooms, and writing cheques to researchers and organisations active in this field.

Cama informed the Parsi community about the disgrace in which historical accounts were lying at the library. It became an extremely emotional discovery for Parsis who came together and donated money and expertise to preserve and restore the library as well as its rich literature. Parzor carried out the restoration project with the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH).

Today, the restored farmans of Mughal emperor Akbar, the three volumes of Shahnama, an epic poem by the 10th century Persian poet Ferdowsi, a khayal by Tansen (still under restoration), letters by Abul Fazal who was Akbar’s grand vizier, and other scholarly work in Persian, Urdu, Gujarati, Avestan, Pahlavi and Sanskrit languages are stored in a tiny air-conditioned room in an annexure at Meherjirana Library. There is nowhere else to store them.

Cama’s efforts have also encouraged young researchers from the community to dedicate their careers to their community’s the conservation cause.

The First Dastoor Meherjirana Library. | Manisha Mondal | ThePrint

UNESCO memory of the world project

A chance conversation in 1999 with Spanish scientist Fredrico Mayor who was the then director general of UNESCO put Cama on the path to discovery. The two spoke at length about the culture, traditions, and heritage of the diminishing Parsi community. The same year UNESCO agreed to sanction $4,500 to a young Cama if she could come up with a project proposal.

“I was told that I would get the money if I could prove that the intangible Parsi heritage is of value to the world, and if the community supported my work,” said Cama. “Back then the world had not understood the value of oral traditions, nor had it realised that we were losing small communities at a rapid pace,” Cama said, sipping Irani tea at her South Delhi bungalow.

Parsi priests across the country gave her letters of support, as did all anjumans and punchayets — governing bodies representing the community. And the Parzor project was born.

“UNESCO’s intangible heritage programme started in 2001, I did my work in 1999. I take pride in saying that I heralded this project!” she said with a smile.

For the last 20 years, Cama has been travelling the length and breadth of India during summer breaks gathering stories, trinkets, and even valuable items. She has collected family portraits, jewellery, recipes, a water filtering system dating back a hundred years, lost songs, sandalwood boxes. She has recorded the processes of making kustis (a sacred Parsi thread), the methods used by bonesetters (chiropractors), as well as torans (a wall hanging made of glass beads), and Parsi embroidery work, among other things.

As Cama continued on her mission, she got support from the government of India, and helped conduct demographic studies on the Parsis, which led to the conception and implementation of the central government’s Jiyo Parsi scheme.

And along the way, she roped in young students, aspiring researchers and photographers to look after various aspects of the preservation efforts. 33-year-old Vanshika Singh, now a PhD scholar, helped in the digitisation of Parsi theatre scripts, while students like Pune-based Freny Daruwalla took up the mantle to record oral histories of members of the community. Ruzbeh Umrigar, a Navsari resident, started conducting heritage tours and walks in Navsari.

Parzor has organised more than 50 photographic and other exhibitions in the country and around the world on Zoroastrian and Parsi culture. They have made movies, published books, conducted workshops on Parsi embroidery, stained glass making and have also made more than 100 presentations on academic and professional writing on Zoroastrian culture and art forms.Digitised Parsi theatre

Vanshika Singh, then 23, was a sharp, ambitious English literature student at Lady Shri Ram College when she did an internship with Parzor. She was entrusted with one of the most interesting projects: collection and digitisation of Parsi theatre scripts written in Gujarati.

In 2012, when she visited Parsi families in Mumbai she was welcomed. Many people entrusted the young woman with family antiquities, and parted with them towards the larger cause of the community’s history and humanity. These include adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays, photographs of old Parsi plays being staged, as well as now long-gone Parsi theatres in Mumbai. Some of the scripts include personal diary of Jehangir Pestonjee Khambata – a thespian of Parsi Theatre, on his voyage to Burma. Other earlier scripts from 1871 to 1875 refer to Harishchandra Natak by KN Kabraji, Jehangir by Adilji Jamshetji.

She interviewed people about the thriving Parsi theatre culture, and returned to Delhi with precious recordings, and two bags full of scripts and photographs on the train back to Delhi.

When I heard the recordings and went through the photographs, I realised the Parsi influence on the development of cities like Mumbai and Kolkata not only shaped them commercially, but culturally as well –

Vanshika Singh, PhD scholar at the National University of Singapore

The digitisation efforts were primarily carried out with the help of the Calcutta Parsi Amateur Dramatics Club and with two separate grants from the Sangeet Natak Ackdemi. Parzor currently has PDFs of digitised scripts in its repository, waiting for a website. Some scripts are with Parzor and some have been returned to the families, according to Singh.

“When I heard the recordings and went through the photographs, I realised the Parsi influence on the development of cities like Mumbai and Kolkata not only shaped them commercially, but culturally as well,” said Singh. “Yes, on the face of it you do have NCPA and other art galleries, but not all developments are grand.”

A lot of the anecdotes and snippets of history she gathered gave her a “micro-view” of the Parsi community and its impact. “You’re left wondering what prompted these communities to create space for cultural expression to thrive,” said Singh who is now doing her PhD in Social and Cultural Geography at the National University of Singapore.

Theatre is an intrinsic part of Parsi cultural identity. It was developed as the earliest form of entertainment, and to date the genre that rules Parsi theatre is comedy. Performed in Parsi Gujarati, they would run ahead of festivals and New Year celebrations, in pavilions set up in colonies or in theatres. But as the Parsi population dwindled, so have these traditions.

“There was a time, till even 5-6 years ago, when I used to perform 5-8 plays before New Year celebrations in Mumbai every year. This year I didn’t even go to perform there,” said theatre actor and Padma Bhushan awardee, Yazdi Karanjia. The living room of his 100-year-old home in Surat is filled with theatre memorabilia and awards earned in his seven decade-long career.

But Karanjia was never a full-time theatre actor. He taught accountancy, much like many members of the community, who continue family traditions and professions, and provide services to the community while working other jobs.

As a boy, his friends would discourage him from pursuing a career on stage– he was too short for any role. But that didn’t stop him from pursuing his love for the performing arts. He goes on stage for the love of his art, not money. And now, some of the plays that he acted in will be part of the repository.

Parsi theatre doyene Yazdi Karanjia. | Manisha Mondal | ThePrint

The scripts were digitised under the advice of scholar Rashna Nicholson, currently professor of theatre studies at University of Hong Kong, and Cama. “Conservatism is expensive but digitisation is not so much. By digitising the scripts, we made them accessible to scholars across India and globe,” Singh said.

Singh and the Parzor team digitised 230 scripts over the course of six months in 2015-16 but they haven’t been able to develop a website for them because they lack the funds and resources to organise such lengthy archival work. Even though the scripts have no online home, word has spread across the world. Filmmakers from Australia and California and scholars from SOAS, London and other universities are reaching out to Parzor for PDFs of the scripts.

Recording and archiving are an important part of the process of documenting Parsi history, but for Singh, the fact that others find value in the work is fulfilling. “It leads to a question I think about. For a community like the Parsis, how can we create meaning? What does it want to circulate about itself or beyond it for us to make sense of its history?” Singh said.

Karanjia is not too worried about the future of Parsi theatre.

“As long as a single Parsi remains on the planet, Parsi theatre shall remain alive,” he insists.

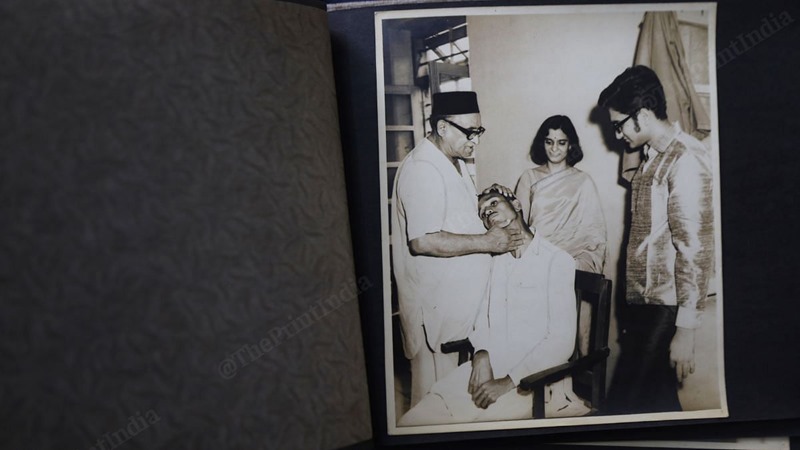

A digitised archive of a photograph of Parsi theatre in action | Parzor and Sangeet Natak Academy Grants

Bonesetters, weavers, actors

Like Karanjia, many Parsis perform a ‘service’ through which they contribute to the larger community. It’s a family tradition that’s not their main source of income.

Among Navsari’s Parsis there are astrologers, weavers, and even bonesetters (chiropractors) who provide people with alternative ways of healing broken bones. There’s no recorded literature of the techniques they employ, but knowledge passed down from father to son over generations.

“I am the eighth-generation bonesetter in my family, and my son is the ninth. My great great grandfather had gained the knowledge from a seer,” said Bezat Minusuraliwalla from Navsari, adding that he served at Mumbai’s Bhatia Hospital for five years though he doesn’t have a degree in medicine.

At his home in Navsari, he pulls out photographs of his ancestors who helped heal bones of people at a time when plasters, especially, weren’t effective. His knowledge and technique are now part of Parzor project archives.

Photo of a Prasi bonesetter. | Manisha Mondal | ThePrint

During one of her many visits to Navsari, Cama recorded how the kusti, the sacred girdle worn by Zoroastrians around the waist, is handwoven by the women of Ava Baug and distributed to other Parsis. Shehnaz Dastoor (50) has been weaving the threads on the mechanised machine at her house for 20 years while humming to old Bollywood music playing in the background.

This is her primary family business–she learnt it from her mother who learnt it from her mother. But her daughters have chosen a different profession, “They don’t enjoy this kind of work. They are well educated and work in MNCs, where they earn significantly more money,” said Dastoor. She weaves the sacred thread for almost 12 hours every day, but is able to earn only Rs 15,000 a month.

As younger generations take up new jobs, recording these traditions becomes even more necessary, said Cama. Only memories will remain, so for archivists like her, there’s an urgency to record.

Oral history recordings

Freny Daruwalla who is in her mid-twenties, grew up in Pune, agnostic of her religion or religious traditions.

“I just didn’t have any interest in it,” she said.

That was until college, when she became more aware about her identity and wanted to get to know more about her community. “I had felt like an outsider till then, not knowing much about my community or participating in cultural events. As I grew older, I wanted to know more about my people.”

In November 2021, Daruwalla started working with Evergreen Story, a platform with a mission to record, preserve and (tell) humanity’s stories and use the medium of storytelling to support the environment.” For every story published, the platform plants a tree in the name of the person documented.

Daruwalla started recording Parsi stories for the platform and has so far met more than 300 Parsis across the country and published their stories. Among her favourite stories are the recording of Mona Jaats, which are hymns sung before any religious function. Only the older generation of Parsis today have knowledge of Mona jaats, which are endangered.

She also interviewed the grandson of one of the last Parsi healers, who were called Va Ujavanu– those who used prayers to heal.

“The Parsis I had interviewed during my oral history recordings are mostly dead now. So Daruwalla is now traveling 20 years after I did to record the experiences of the younger generations,” Cama said.

The memories and micro-histories of Parsis are rich in vignettes and encounters with India’s elite. India’s first woman photojournalist Homai Vyarawalla who passed away in 2012 spoke to Cama at length about her interactions with the Gandhis. And one project that she could never forget was the wedding of Rajiv Gandhi with Sonia. Vyarawalla was paid for the photographs and the negatives. She never got to see her work again. “But it was all in her memory,” said Cama. And now, in Parzor’s oral history archives.

Photographers from other communities also document the Parsis, their distinct culture and dying heritage that piques the interest of many, like that of Bindi Sheth who put up her photo exhibition at India International Centre in Delhi. Bindi documented the Parsis in her hometown, Ahmedabad.

The themes that stand out in her exhibition are loneliness, love, loss and celebration, as well as a lingering influence of the British. There are photographs of young bachelor Parsis living in baugs, of older Parsis alone in old houses filled with antique furniture, and of families gathering for weddings and Navjotes.

The library makes appeals to the Parsi community on an annual basis and asks for donations for restoration, preservation work. That’s our main source of income

– Chaitali Desai, Librarian at Meherjirana

“As an outsider, I realised I have the advantage of noticing minor details like their love for natural elements that set them apart and make them a unique, intriguing community,” she said.

Ruzbeh Umrigar, who conducts heritage walks in Navsari, remembers spending his summers in the hall of the then crumbling Meherjirana library. He had no clue about the importance of the literature the library has. It was only many years later, after Cama’s discovery, that he learned about the rich texts lying in the cupboards of one of his childhood haunts.

Today, the library has an annexe, and a trust board has been set up to look after its day-to-day functioning. According to the current librarian, Chaitali Desai, it doesn’t get government support, but runs on charitable donations.

“The library makes appeals to the Parsi community on an annual basis and asks for donations for restoration, preservation work. That’s our main source of income,” she said.

The library’s collection and contribution to the community’s heritage is a source of pride for her. There are more than 600 handwritten Parsi scriptures, Desai said.

“The restoration of the Meherjirana library is one of the biggest achievements of Parzor. And not only have all books been preserved, they have also been digitised,” Cama said. “When I first went there, the books couldn’t even be touched.”

Now that it is back in the limelight, the library’s future is caught in the local politics of who gets to run it. Its responsibility currently lies with a trust which is not comprised of academics. Some Navsari residents fear that lack of scholars or academics puts these records in jeopardy.

But even as these battles are playing out in the upper echelons of the community, the younger generation is looking at ways to add to the work archived and documented so far. School teacher Pinaz (27) got the opportunity to work with Parsi author and historian Marzban Jamshedji Giara. She assisted him on the research of his last book, Prominent Parsis of Navsari, which was published a year after he passed away in 2022. And since then, Pinaz has been a little directionless.

“I need to be financially independent, I haven’t been able to work out a model where I research and document but also earn money at the same time,” she said adding that “it is very important to record contemporary Parsi stories, otherwise us and our stories will die in the little circle orthodox of our community want to restrict us to.”

Freny Daruwalla has lived through countless personal histories. The Parsis she interviewed shared their experiences of watershed moments—the red dots in history. Ninety-year-old Tina Mehta’s heart is still heavy with the memory of the last time she kissed her Muslim friends goodbye during Partition in 1947. Daruwalla heard the heartbreaking account of Ahmedabad resident, Hafiz Dalal, who frantically searched for his daughter when Gujarat went into curfew during the 2002 riots. She has felt the frustration of Dilshad Mistry, who was called to office within two days after the infamous floods in July 2005 that left Mumbai flooded.

These oral histories have made Daruwalla a time traveller.

“It feels like people are not talking from memory at all. The story just flows out of them naturally, like they’re living through it in real time.”