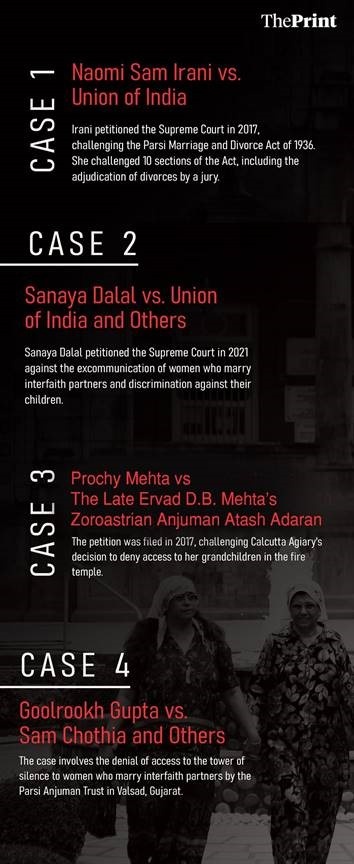

Marriage, divorce, inheritance, and temple rights are all skewed in favour of men. Four Parsi women see UCC as an equaliser but Bombay Parsi Punchayet wants ‘total exemption’.

People at agiyari (fire temple) on Navroze, which is Parsis’ new year | Photo: Manisha Mondal/ThePrint

Article by Shubhangi Misra | The PRINT

Delhi/Mumbai: A viral message circulating within Parsi WhatsApp circles has become the most hotly debated topic within the closely knit community. It is a photograph of the trustees of the Bombay Parsi Punchayet alongside Justice Ritu Raj Awasthi, the chairperson of the 22nd Law Commission of India. For an hour and a half on 21 August, a delegation from one of India’s most powerful Parsi organisations presented their case before the government—the complete exemption of Parsi-Irani-Zoroastrians from the Uniform Civil Code.

“We seek total exemption from the UCC, especially since exemption for some tribes is being considered,” a trustee of the Bombay Parsi Punchayet (BPP) told ThePrint.

But the winds of change that the Uniform Civil Code (UCC) threatens to herald have exposed fault lines within the seemingly homogeneous Parsi community, and at the forefront of this movement are four women. They are fighting for their own rights and those of their children against “archaic” laws that were established at a time when women had no rights, and they predate the Constitution of India.

Marriage, divorce, inheritance, and temple rights are currently skewed in favour of men. These women see the UCC as an equaliser, one that offers them a chance to be on equal ground with men.

“The Uniform Civil Code will bring laws that will treat all genders equally. It is very important for Parsi women, so discrimination against us on the basis of centuries-old observations can finally end,” says author Prochy N Mehta.

Since Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s statement that a country cannot function with dual systems of separate laws for separate communities and the 22nd Law Commission began public consultations on the UCC, Parsis have joined the debate alongside Muslims, Christians, and tribal communities across the country.

Within the Parsi community, orthodox members worried about purity, bloodlines, and tradition want to preserve the old ways, while the more progressive members are rooting for change. Both sides are writing open letters and op-eds, pinging each other in WhatsApp groups, discussing it over dinner at their homes, and arguing about it within the confines of their walled enclaves.

The Uniform Civil Code will bring laws that will treat all genders equally. It is very important for Parsi women, discrimination against us on the basis of centuries-old observations can finally end —

author Prochy N Mehta.

Photo: Manisha Mondal/ThePrint

“If UCC is implemented, it will infringe on the traditions of our peaceful community. Then, anyone will be able to enter the fire temple, and adoptions will be allowed in the Parsi community, which we can’t accept,” the BPP trustee said.

A storm is brewing, and even Parsi High Priest Dasturji Khurshed Dastoor has been drawn into its vortex. Reports suggesting his support for the UCC have angered prominent Parsis. Dastoor subsequently issued a statement clarifying that he had been misquoted. “I have not said that Parsis would welcome UCC, nor do I feel that UCC will be welcomed by the Parsi community,” he was quoted as saying in The Free Press Journal.

But this time, the women within the community have decided they won’t be accepting these diktats. They have filed petitions in courts challenging practices they see as discriminatory, with the UCC serving as an impetus to their cause.

If UCC is implemented, it will infringe on the traditions of our peaceful community. Then, anyone will be able to enter the fire temple, and adoptions will be allowed in the Parsi community, which we can’t accept — the Bombay Parsi Punchayet trustee

Prochy Mehta petitioned the Kolkata High Court after her grandchildren were denied entry into Kolkata’s Fire Temple. Goolrukh Gupta has challenged the decision of the Valsad Parsi Anjuman to bar her from performing her mother’s last rites since she married outside the community. Gupta argues that her rights under Article 21 and 14 of the Constitution have been violated. Sanaya Dalal, a former journalist, petitioned the Supreme Court in February 2021 against gender discrimination perpetuated by certain Parsi institutions, especially the Parsi Colony Gymkhana in Dadar, against women by not admitting children of those who marry outside the faith. Dalal’s five-year-old son has been barred from entering the playground at the Dadar gymkhana. And sculptor Naomi Irani petitioned the Supreme Court challenging several sections of the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act 1936. She is the only one to do so.

“Why is my marriage governed by 100-year-old laws?” asks Irani, who filed for divorce in 2016. Even after seven years, her divorce has not yet been finalised.

Photo: Manisha Mondal/ThePrint

Also read: Parsis are choosing between extinction and purity. It’s not always a pretty choice

Court cases drag on

Every time, Naomi Irani stepped into the Bombay High Court, she felt as if the walls of the 150-year-old heritage building were closing in on her, as though ready to swallow her completely. It’s where a jury of five prominent Parsi men and women should have been convening to deliberate her case, but so far it hasn’t assembled even once.

The Irani-Parsi-Zoroastrian community is the only group in the country whose divorce cases are adjudicated by a five-member jury in the Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras High Courts, as per Section 18 of the Parsi Matrimonial and Divorce Act of 1936. Remarkably, these Parsi matrimonial courts are India’s last surviving jury trials—decades after India did away with them in 1959. The Act was amended in 1988 to recognise mutual consent as a valid ground for divorce.

More often than not, the panel members are senior citizens, and coaxing them to attend courtroom sessions can take years, according to Irani, the frustration leaking into her voice.

The jury panel members are appointed by the Bombay Parsi Punchayet and they participate in the proceedings, rendering judgement in line with the judge’s decision. If the jury’s opinion diverges from the judge’s verdict, the judgment becomes void, explained Firoza Daruwala, one of Irani’s counsel in the Supreme Court.

“There’s absolutely no privacy. The dirty linen of our marriage is washed in front of a small community, where news travels fast,” laments Irani. Supreme Court lawyer Firoza Daruwala likens the proceedings to a TV serial.

Photo: Manisha Mondal/ThePrint

Cases often drag on for years. At the Bombay High Court, Irani met many people struggling to get a divorce for over a decade.

Unlike family courts, which specifically deal with familial issues and marriage-related conflicts, the same conducive environment in absent on the high courts, which can be a gruelling experience for families.

To sidestep these protracted legal processes, many couples reach an understanding outside the courtroom, a situation Irani labels as “justice denied.”

“Our divorce cases stretch for decades. This personal law is discriminatory towards women. This is why I have challenged it,” says Irani.

She is the first woman from the Parsi community to challenge ten sections of the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act 1936 and petition the Supreme Court for the abolishment of the jury system. Among the sections she contests is Section 50, which stipulates that if a Parsi wife commits adultery leading to a divorce or judicial separation, the court might “settle” half of her property “for the benefit of the children”. The provision doesn’t apply equivalently to men.

In 2017, when she stood before the Supreme Court, she felt liberated. Accepting her petition, the bench of Justice Kurian Joseph and Justice Amitava Roy asked why such a law has not been challenged so far. “One voice is still a voice,” Irani’s then–counsel Neela Gokhale, now a judge in the Bombay High Court, replied to the bench.

Photo: Manisha Mondal/ThePrint

Who is a Parsi?

A phone call from the Parsi agiyari (fire temple) in Kolkata led Prochy N Mehta down the path of defining Parsi identity. Despite her daughter’s marriage to a non-Parsi, their children are being raised in the Parsi faith. Together, the family often visited the Kolkata Agiyari—the only one in the city—to offer prayers, particularly on special occasions like birthdays, anniversaries, and Navroze (Parsi New Year).

And then the priest of the temple changed and decreed that her grandchildren—offspring of interfaith marriage—would not be allowed inside the temple. Children of women who marry non-Parsis are not accepted into the fold.

Mehta wrote letters to members of the Parsi community in Kolkata, receiving hundreds of replies expressing solidarity. “We have only 30 Parsis below the age of 20 in Kolkata. Everyone here loves children, and nobody wants to alienate them,” she says.

It also set her on the path to try and define the Parsi. She went through old records, spoke to religious and legal experts, and in 2022, published, ‘Who is a Parsi?’— a scholarly work featuring a foreword by jurist Fali S Nariman, which attempts to set the record straight.

Photo: Manisha Mondal/ThePrint

Through her research, Mehta tries to show that there is no legal, religious or social justification for depriving her maternal grandchildren of privileges accorded to Parsis. This extends beyond places of worship to include dakhma (tower of silence) and participation in funeral rites. Her conclusion? Being a Parsi and a Zoroastrian are inherently the same. However, orthodox Parsis do not subscribe to this view.

“Anyone can convert to the Zoroastrian faith but they can’t become Parsi Zoroastrians,” reiterated the BPP trustee.

Mehta’s book has become an integral part of the UCC debate.

For over 12 years now, she and her family have not stepped inside the Kolkata Agiyari. “Why should we go somewhere our children are not allowed?” she asks. Mehta has petitioned the Calcutta High Court against this discriminatory practice.

“How can you refuse to accept the children of women? There’s nothing which says our children will or should not be accepted.”

The origins of these stringent laws trace back to a 1908 case when the first Parsi Bombay High Court judge, Dinshaw Davar, and British judge Frank Beaman observed that Indian Parsis constitute a “pure” caste that need not accept individuals who might “contaminate” the community. However, children of Parsi fathers and “alien” mothers do not face discrimination. Parsis consider the 1908 Davar Beaman judgment as their personal law.

Observations made by these judges are often cited by Parsis to make a case for certain practices, including restrictions at the fire temple or the tower of silence. “Whatever we do, we do as per what the law says,” a trustee of BPP said.

These restrictions frequently seem discriminatory towards women. For instance, while even illegitimate children of male Parsis are recognised as members of the community, the same status is not accorded to children of Parsi women who marry outside the community.

Photo: Manisha Mondal/ThePrint

This is why Goolrukh Gupta from Valsad, Gujarat, was denied entry into the tower of silence to conduct her mother’s last rites by the Parsi Anjuman Trust. Her choice of a non-Parsi husband stripped her of her Parsi rights. Her appeals to enter the Valsad fire temple and the doongerwadi (site for death rituals) were rejected. She petitioned the Gujarat High Court, which ruled against her. Subsequently, she approached the Supreme Court, asserting that the ban violates women’s rights enshrined under Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution.

“The 1908 Davar Beaman document is an observation, not a law. It is from an era when women weren’t even considered individuals, and it predates the Constitution. It is 110 years old and should not be referred to,” said Dalal.

No adoption allowed

Within the now defunct Parsi Lying-In Hospital in Mumbai’s Fort area, only one ward remains occupied. It’s not filled with babies or nurses or doctors; rather, it’s the workplace for the small team behind the fortnightly magazine, Parsiana. The work tables are cluttered with a trove of old issues, newspapers, magazines, files, and papers.

As the debate on UCC heats up, Parsiana has published both sides of the argument. Its editor Jehengir Patel, who has heard all sides and fractions, holds a ‘moderate’ stance. “Reform should come from within; it cannot be imposed,” he says. But many fear that it may be too late already. Patel wants Parsis to shed their orthodox practices but doesn’t think a hasty Uniform Civil Code is the solution.

As the Parsi population dwindles, adoption is not considered a solution. As per the 1908 Davar-Beaman judgment, the adoption of a ‘foreign child’ cannot integrate them into the Parsi community.

“A Parsi born must always be a Parsi, no matter what other religion he subsequently adopts and professes. He may be a Christian Parsi, and he may be any other Parsi, according to the religion he professes; but a Parsi he always must be,” notes the judgment.

Photo: Manisha Mondal/ThePrint

Berjis Desai, advocate and author of Oh Those Parsis!, highlights how this has put young Parsi couples in a bind. “Many want to adopt a child. But in the absence of any legal authority, they’re unable to do so,” he said.

Desai explains that some Parsi couples have adopted children under the Guardians and Wards Act 1890, becoming legal guardians and gradually integrating them into the community. “But the tag of being recognised as a parent is desirable,” he adds. Other communities, such as Muslims and Christians, also adopt children under the same Act, but these adopted children do not enjoy the same status as naturally born children.

In an op-ed published in Parsiana, Desai illustrates this with the example of a Parsi couple who adopted their domestic worker’s child. While she lived in a BPP housing complex and embraced the baug culture, even undergoing a Navjote ceremony, none of these actions guaranteed her rights as a Parsi.

“Unlike adoption, where the adopted child automatically acquires the same status as a natural-born child, the Guardians Act does not confer similar legal status. For instance, if the guardian parent dies without a will, his child under the Guardian Act will not have the same inheritance rights to his estate as his natural born would,” Desai wrote.

In all likelihood, the adopted child won’t be entitled to live in the BBP flat within the baug she grew up in because she is not considered a Parsi.

“Forget wards, even children of women who intermarry cannot reside in baug flats. The presence of a will doesn’t make a difference,” said advocate Firoza Daruwalla.

Total exemption

Within the Parsi community, there’s a growing discontent over what is seen as the Bombay Parsi Punchayet’s emergence as the deciding voice in the Uniform Civil Code debate.

Who gave them the power to represent the community during its meeting with the 22nd Law Commission of India, asks Desai.

“Was expertise the reason for selection, or their religious views? The grapevine has it that several who were invited did not attend, including Udvada High Priest Dastur Khurshed Dastoor, former member of the National Commission for Minorities,” he wrote in a barbed criticism in Parsiana. Desai further asserted that no liberal voices were present in the meeting. “The consultations appear to be orchestrated to reach the conclusion desired by the trustees, namely, total exemption. Not a single cogent reason was given for such total exemption other than to preserve religious customs and beliefs.”

Liberal Parsis argue that while the orthodox faction is vociferous, they represent a minor perspective on reforming the community’s doctrine. Despite their small numbers, though, the orthodox hold authoritative positions, including religious leadership, which prevents reform.

People at agiyari (fire temple) on Navroze, which is Parsis’ new year | Photo: Manisha Mondal/ThePrint

The UCC has brought these practices into the public gaze.

The 2018 Law Commission of India report on family law reform criticised the jury system as “archaic”, “tedious”, and “complicated”. The report highlighted the infrequency of jury sessions, with juries meeting only twice a year. And since Parsi Matrimonial Courts are set up only in presidency high courts, it causes inconvenience to people residing far from metropolitan areas.

“Not only does this cause inordinate delays and inconvenience to people living outside metropolitan cities, but also these systems discourage inter-community marriage.” According to advocate Daruwala, the Parsi matrimonial court attached to the Bombay High Court hasn’t been held since August 2019.

At the Dadar Parsi Gymkhana in Mumbai, the sounds of children playing can often be heard over the beep and blare of traffic noise. It’s where Dalal’s son would go to play with his colony friends. But when he turned five, he was barred from entering the playground because he was the child of an interfaith couple. Children of women who marry outside the community are prohibited from using the gymkhana. He is facing the same discrimination that his father Rishi did when he was growing up. Rishi’s parents were also an interfaith couple.

“This is second-generation discrimination,” says Daruwala, a childhood friend of Rishi’s, and Dalal’s counsel. “All his life, Rishi was left behind at cultural events and [stopped] from offering prayers at the agiyari. Today, the same thing is happening to his son.”

Ever since Dalal moved the courts, she’s been receiving hate comments on social media. Detractors, who Dalal says should be ‘detained’, call her son and other children of inter-faith marriages as ‘diluted milk’, ‘mules’, and ‘bhelpuri’.